Hooey About Louis: The "Jazz World" vs. Louis Armstrong

This is a post I've thought

about doing for several years but never had the energy to put together, mostly

because it consists of ground already covered in my two books. However, I think

the time is right to run with it because of Michael Ullman's review of my new

book, Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong,

received last week in ArtsFuse.

Let me get all disclaimers out of the way first: it's a very positive review, for which I am grateful for, and I respect Ullman as a historian and critic so what I'm about to write isn't personal. However, in the first half of his review, he took me to task for presenting an "unconvincing" argument that the mysterious "jazz world" was against Louis Armstrong and doesn't buy my contention that Armstrong "was 'vilified' by jazz fans and the jazz press." No, Ullman argues, economics were a bigger obstacle than “the jazz world” and besides, my argument is contradicted by the many positive quotes I include from jazz musicians during Armstrong's lifetime. And ultimately, Ullman himself attended an Armstrong concert and those present--"jazz fans all"--enjoyed it, plus "every critic" Ullman knows agrees on Armstrong's best recordings in this period.

Ullman tries to discredit my argument by focusing on "jazz fans" and "jazz musicians," but never goes as far as discussing the jazz press. And that's where this blog comes in. Over the course of my 25 years of studying Armstrong (this week's the anniversary of the “big band”!), I have become numb to all the invective hurled at Armstrong over the years, especially during his lifetime. I've collected the best (worst?) of it in my books and can admit that reading so many wrongheaded assertions is what sent me on my path when I was still in high school. I don't engage in hagiography but am driven by letting Armstrong defend himself with his own words.

That won't be the case today. Over the next several thousand words, I will paint an admittedly one-sided picture of the overwhelming negativity spewed by specifically the jazz press since the early 1930s. I'm leaving out the black press, the newspaper columnists and the music trades and I'm (largely) leaving out the musicians (though they will come through later). And let it be said right up front, that Armstrong always did have his defenders, including Dan Morgenstern, Ralph J. Gleason and many others during his lifetime so I know what I’m presenting is one-sided, but these are the dominant, most widely-read stories of that era.

This post will be serve as

a reminder that Louis started catching hell just a few years after his epochal

1928 recordings and had to spend the last 40 years of his life hearing mostly

from white jazz critics telling him that all of his choices were wrong: his

trumpet playing, his singing, his showmanship, his solos, his recordings, his

repertoire, all of it wrong, wrong, wrong. Hell, I'm sure there are some people

who feel that way and others who will read some of the below reviews and think,

"Well, that makes sense." That's fine, but not the point of cobbling

all of this together. Consider this a one-man Louis Armstrong version of

Nicolas Slonimsky's Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on

Composers Since Beethoven's Time. (The late Michael Cogswell introduced me

to that work; if you don't know it, check it out.)

Needless to say, there

wasn't exactly a "jazz press" in the United States when Armstrong was

changing the world in the 1920s, but Melody Maker in England was

definitely picking up on what Armstrong was doing by the end of 1929 and

devoted issue-after-issue to gushing reviews of his recordings in the next

couple of years. In early 1932, Melody Maker hired John Hammond to write

a column detailing what was happening in the States, or as they put it,

“Slashing Comments on American Bands and Musicians.” In his second column, from

March 1932, Hammond called Armstrong's recording of "Home"

"absolutely atrocious,” adding, "It must be fairly obvious by now

that the band should be changed, particularly in piano and brass departments."

One month later, in a column titled "The Decline of Earl Hines"

(“About five years ago, when he was recording with Armstrong, Hines had the

enormous advantage of simplicity coupled with astonishing ingenuity. Now he

seems merely a showman, and a most flashy one at that.”), Hammond wrote of

Armstrong's performance at the Lafayette in Harlem, "Every show is

different: he is original beyond belief. Unfortunately, he is almost killing

himself by hitting high C about two hundred times in succession at the

conclusion of ‘Shine,’ all for no reason whatsoever. Sometimes he does this

three and four times a day, and then drops dead.”

The summer of 1932 was spent in England, the subject of an entire chapter of Heart Full of Rhythm so I don't feel the need to recap it here (needless to say, most of the reviews were very racist). The most interesting takeaway for me is the British jazz writers such as Edgar Jackson and Spike Hughes who worshipped Armstrong's OKeh recordings (issued there in Parlophone), began changing their tune after spending four months watching him on stage. An October 1932 Melody Maker review of the Parlophone coupling of "Them There Eyes" and "When You're Smiling" referred to it "nearly the worst couple of titles Armstrong has ever made, adding, "The main trouble is to reconcile the Armstrong of the stage with the Armstrong of the records before his appearance over here. It is all very difficult and worrying, for it means revising one’s whole attitude towards his records, an attitude which is the result of several years’ listening and study. So sad."

Armstrong returned to

England in the summer of 1933, spending much of the trip listening to records

with John Hammond. "Not that Louis and I

always agreed. We had violent disagreements on such subjects as the Majestic’s

evaporated milk, food, his new records, his old records; in fact, almost

everything. But we did have just enough in common to get along gorgeously. Both

of us were united in feeling that his best discs were made in the Earl

Hines-Redman days of super-ensemble-and-accompaniment. As to his newly acquired

showmanship, there still remains a marked difference."

Armstrong opened at the Holborn Empire in London and immediately drew the ire of Percy Brooks of the Melody Maker, who published his review with this incredible headline:

Armstrong opened at the Holborn Empire in London and immediately drew the ire of Percy Brooks of the Melody Maker, who published his review with this incredible headline:

AMAZING RECEPTION FOR ARMSTRONG

FRENZIED APPLAUSE FOR MEANINGLESS PERFORMANCE

Louis Deliberately All Commercial

FRENZIED APPLAUSE FOR MEANINGLESS PERFORMANCE

Louis Deliberately All Commercial

"Only the ringing down of the

curtain and the playing of “The King,” by the pit orchestra stifled the fervid

applause. But Louis must have caused many of his most enlightened supporters to

sorrow for him. His act was fifty per cent showmanship, fifty per cent

instrumental cleverness, but about nought per cent music.

He seems to have come to the conclusion that a variety artists only mission in life is to be sensational, to pander to the baser emotions, to sacrifice all art to crude showmanship; this from the most admired and outstanding individual dance musician in the world!

[...]

Later he announced 'Shine,' introduced by the band with an intriguing short phrase which Louis made it repeat perhaps a dozen times. This effective opening, however, flattered only to deceive, for the number was used merely to permit Armstrong to blow, unaccompanied and ad lib, a series of seventy high C's, culminating in a top F, a feat of endurance which caused many of the fans to cheer ecstatically, but which made the more thinking members of his audience ask themselves, 'Why?'

His whole show was more or less like this; mere gallery playing. Only a few notes and phrases here and there made one realise that his sheer musical ability still exists, although now subjugated to a policy of ostentatious showmanship.

Unwise Showmanship

Throughout it all, Louis sweated as unnaturally as of yore, and, in fact, he deliberately drew attention to it with by-play with handkerchiefs and even more pointed references.

It is not his fault that his nervous system causes this immense perspiration and, in fact,when he is playing real music one takes little or no notice of this physical reaction, but it is a commentary on the Armstrong of to-day that he endeavours to make capital out of it.

Shall we never hear Louis Armstrong on a London stage supported by a first-class band and playing music for intelligent people? Or is this an end to him as a pioneer and a pattern?

What a dreadful shame, and what a wicked waste."

He seems to have come to the conclusion that a variety artists only mission in life is to be sensational, to pander to the baser emotions, to sacrifice all art to crude showmanship; this from the most admired and outstanding individual dance musician in the world!

[...]

Later he announced 'Shine,' introduced by the band with an intriguing short phrase which Louis made it repeat perhaps a dozen times. This effective opening, however, flattered only to deceive, for the number was used merely to permit Armstrong to blow, unaccompanied and ad lib, a series of seventy high C's, culminating in a top F, a feat of endurance which caused many of the fans to cheer ecstatically, but which made the more thinking members of his audience ask themselves, 'Why?'

His whole show was more or less like this; mere gallery playing. Only a few notes and phrases here and there made one realise that his sheer musical ability still exists, although now subjugated to a policy of ostentatious showmanship.

Unwise Showmanship

Throughout it all, Louis sweated as unnaturally as of yore, and, in fact, he deliberately drew attention to it with by-play with handkerchiefs and even more pointed references.

It is not his fault that his nervous system causes this immense perspiration and, in fact,when he is playing real music one takes little or no notice of this physical reaction, but it is a commentary on the Armstrong of to-day that he endeavours to make capital out of it.

Shall we never hear Louis Armstrong on a London stage supported by a first-class band and playing music for intelligent people? Or is this an end to him as a pioneer and a pattern?

What a dreadful shame, and what a wicked waste."

******************************

Apparently, Armstrong toned

it down the following week at the Palladium, winning praise from Brooks in the

August 12, 1933 issue of Melody Maker:

"Critics of dance music agreed

that Louis had “gone off”--sacrificed his art (for art it undoubtedly is)

to “fetching” the gallery. This performance, coming on top of the issue of a

shockingly bad 12-in. Medley of Armstrong tunes, seemed to indicate that the

star was waning.

But Louis listened to the well-meant criticism. Of all big-timers Louis has the least “side.” He realised that his severest critics were really his best friends.

In America an appreciation of what is good in dance music is even rarer than it is here. Although the best bands and players are in America and on the air daily, the great American public is even more dumb than the great B.P.

Artists of dance music, who really know what it is all about, have to play down to a public that just wants cheap sensation and belly-laughs.

Gradually, therefore, Armstrong had slipped, perforce, into giving the American public what everyone told him it wanted. He overlooked the fact that it was just because he was “different” that his audiences sat up and noticed him in the first place.

His clowning had “got” them there in the States and therefore was it not logical to believe that it would “get” them here?

But Louis overlooked the astonishing fact that the Holborn (and the other theatres he will play) would be filled every house with fans, their friends and the acquaintances the fans have brought in out of curiosity to see the “black man young Joe raves about.”

He is playing, every night and every house, to a fan public.

[...]

It is to this faithful fan audience, then, that Louis has to play in this country. Whatever he did would be right for most of them.

Louis, therefore, was leaving only one small section dissatisfied--the dance music critics.

Louis knew, in his heart of hearts, that they were right in condemning his performance.

So from the Tuesday onwards, he began to play--properly.

[...]

And we really sincerely hope that he will pursue his changed tactics.

The world’s greatest trumpet player must not be allowed to deteriorate, even if we have to club him over the head to stop it.

So take warning, friend Louis!"

But Louis listened to the well-meant criticism. Of all big-timers Louis has the least “side.” He realised that his severest critics were really his best friends.

In America an appreciation of what is good in dance music is even rarer than it is here. Although the best bands and players are in America and on the air daily, the great American public is even more dumb than the great B.P.

Artists of dance music, who really know what it is all about, have to play down to a public that just wants cheap sensation and belly-laughs.

Gradually, therefore, Armstrong had slipped, perforce, into giving the American public what everyone told him it wanted. He overlooked the fact that it was just because he was “different” that his audiences sat up and noticed him in the first place.

His clowning had “got” them there in the States and therefore was it not logical to believe that it would “get” them here?

But Louis overlooked the astonishing fact that the Holborn (and the other theatres he will play) would be filled every house with fans, their friends and the acquaintances the fans have brought in out of curiosity to see the “black man young Joe raves about.”

He is playing, every night and every house, to a fan public.

[...]

It is to this faithful fan audience, then, that Louis has to play in this country. Whatever he did would be right for most of them.

Louis, therefore, was leaving only one small section dissatisfied--the dance music critics.

Louis knew, in his heart of hearts, that they were right in condemning his performance.

So from the Tuesday onwards, he began to play--properly.

[...]

And we really sincerely hope that he will pursue his changed tactics.

The world’s greatest trumpet player must not be allowed to deteriorate, even if we have to club him over the head to stop it.

So take warning, friend Louis!"

******************************

By this point, Armstrong's

RCA Victor recordings were being issued in England. Spike Hughes heard glimmers

to praise, but more to criticize. Here he is on "Mississippi Basin"

in the October 21, 1933 Melody Maker:

"For the first minute or so of this first side of

Louis’ ‘Mississippi Basin’ it really seems that Louis has ‘come home, all is

forgiven.’ In short, Louis Armstrong has not played in this unspectacular

fashion for more records than I (and I hope others) care to remember. The first

twenty-four bars of the chorus, as Louis plays them, might have been recorded

in his dressing-room. There is no funny business, no terrific striving and

straining. It is all very easy, lazy, and, above all, tasteful playing. But, of

course, not (according to the master himself) playing for the musicians;

the musicians must have lots of high notes, break-neck tempo and noise; playing

quietly, as he does on this record, is almost commercial--for the folks who

aren’t musicians.

How mistaken Louis is in this! He must surely have realised by now that high notes do not impress a musician; he thinks his fans are musicians, but very few of them are. If they were, then the fans would listen to records like ‘Muggles’ and ‘Basin Street Blues’ and ‘Tight Like This’--not to the rowdy ‘Tiger Rags’ and ‘You Rascal You,’ played one-in-a-bar.

[...]

"Miss. Basin," for the first half of the record, then, is the real Louis Armstrong. The vocal refrain is good enough, provided you can understand what on earth he is singing about. The diction in this part is so indistinct that it might be one of Louis’ imitators. There is a sudden fading in the recording at the beginning of this vocal passage which does not help things much either.

But then--

The whole effect is ruined by a completely meaningless coda. High notes, achieved amid much puffing and blowing, which destroy the whole atmosphere, which has so carefully been built up from the very first bar. It is incongruous, unnecessary and completely lacking in taste.

If you are wise and not impressed by the inevitable (as it seems nowadays) showing off with which Louis feels impelled to finish his records regardless of theme or mood, then you will not play this record any further than those exquisite bars of piano playing which follow the vocal refrain.

If you do, you will immediately hear Louis playing a couple of bars which were great when he first played them four years ago, but which have now, in his hands, degenerated into the most platitudinous phrase in the musical vocabulary of trumpet players."

******************************

In January 1934, Hughes reviewed Armstrong's 1930 recording of "Dear Old Southland," calling it "Armstrong's Best Ever." In just four years, Hughes was now longing for the "good old days," writing, "Now, as you have guessed, ‘Dear Old Southland’ is getting on in years, but it dates from one particular period when Armstrong was well-nigh infallible. He played good numbers--never commercial songs in those days--he was spontaneous and grand himself, and his accompaniment was always by good people."

How mistaken Louis is in this! He must surely have realised by now that high notes do not impress a musician; he thinks his fans are musicians, but very few of them are. If they were, then the fans would listen to records like ‘Muggles’ and ‘Basin Street Blues’ and ‘Tight Like This’--not to the rowdy ‘Tiger Rags’ and ‘You Rascal You,’ played one-in-a-bar.

[...]

"Miss. Basin," for the first half of the record, then, is the real Louis Armstrong. The vocal refrain is good enough, provided you can understand what on earth he is singing about. The diction in this part is so indistinct that it might be one of Louis’ imitators. There is a sudden fading in the recording at the beginning of this vocal passage which does not help things much either.

But then--

The whole effect is ruined by a completely meaningless coda. High notes, achieved amid much puffing and blowing, which destroy the whole atmosphere, which has so carefully been built up from the very first bar. It is incongruous, unnecessary and completely lacking in taste.

If you are wise and not impressed by the inevitable (as it seems nowadays) showing off with which Louis feels impelled to finish his records regardless of theme or mood, then you will not play this record any further than those exquisite bars of piano playing which follow the vocal refrain.

If you do, you will immediately hear Louis playing a couple of bars which were great when he first played them four years ago, but which have now, in his hands, degenerated into the most platitudinous phrase in the musical vocabulary of trumpet players."

******************************

In January 1934, Hughes reviewed Armstrong's 1930 recording of "Dear Old Southland," calling it "Armstrong's Best Ever." In just four years, Hughes was now longing for the "good old days," writing, "Now, as you have guessed, ‘Dear Old Southland’ is getting on in years, but it dates from one particular period when Armstrong was well-nigh infallible. He played good numbers--never commercial songs in those days--he was spontaneous and grand himself, and his accompaniment was always by good people."

January

1934 also marked the Melody Maker debut of young Leonard Feather. In one

of his first columns, Feather interviewed composer and bandleader Reginald

Foresythe for a piece titled "No Future for Hot Music." Here's their

exchange on Armstrong:

Feather: Well, now, let’s look at some of the other great solo men and see if they don’t show that busking is the backbone of jazz. If we can show that, we can show why jazz hasn’t advanced, because premeditation and spontaneity are like work and play--they don’t mix. Now, take Armstrong.

Feather: Well, now, let’s look at some of the other great solo men and see if they don’t show that busking is the backbone of jazz. If we can show that, we can show why jazz hasn’t advanced, because premeditation and spontaneity are like work and play--they don’t mix. Now, take Armstrong.

Foresythe: Louis is a great artist to this

day--not because of his high notes and stunts, not even because his technique’s

improved--perhaps it’s deteriorated--but because his playing is governed more

by his intellect. His most enjoyable records, for instance, were the group he

made comparatively recently, with Les Hite’s Band, such as ‘Shine’ and ‘Just a

Gigolo.’ Good arrangements and supporting band, as well as good work by Louis

himself. There you have the epitome of his art: it represents the mental

influence on the spontaneous.

Feather: Personally, I’d a thousand times sooner

hear anything from the grand old Hines-Redman days. ‘Muggles’ and ‘Save It,

Pretty Mama,’ and all those were just superb.

This was the start of

Feather's mission to educate his readers about "the grand old

Hines-Redman" days, writing numerous columns in 1934 that blasted both the

early Hot Fives and the latest big band recordings (“booming, pretentious

orchestrations of 1933”) at the expense of Armstrong's 1928 output.

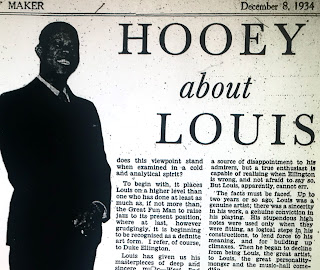

Feather's columns in this period, even when knocking various Armstrong eras, clearly had respect for the trumpeter, who befriended young Feather in this period. The same could not be said for R. Edwin S. Hinchcliffe, who published "Hooey about Louis" in the Melody Maker on December 8, 1934:

"Perhaps no person in the whole world of jazz arouses such deep controversy as “Satchmo.” He is either reviled beyond reason, or deified beyond reason, and few people attempt to get a true perspective on his powers.

An article in a contemporary describes him as the genius of jazz; the greatest of all hot soloists. This is typical of the overstatements which his frenzied admirers are constantly letting loose about their idol, for, according to them, he is the most significant and outstanding figure in the world of jazz. How does this viewpoint stand when examined in a cold and analytical spirit?

To begin with, it places Louis on a higher level than one who has done at least as much as, if not more than, the Great Fun Man to raise jazz to its present position, where at last, however grudgingly, it is beginning to be recognized as a definite art form. I refer, of course, to Duke Ellington.

[...]

The facts must be faced. Up to two years ago, Louis was a genuine artist; there was a sincerity in his work, a genuine conviction in his playing. His stupendous high notes were used only when they were fitting, as logical steps in his constructions, to lend force to his meaning, and for building up climaxes. Then he began to decline from being Louis, the great artist, to Louis, the great personality-monger and the music-hall comedian.

Going Up On Top

Examining his later records, what do we find? A striving after unnecessary top-notes--not always too successfully reached; breaks that are exaggerated and in all too many cases, not particularly rhythmic. And, worst of all, a patent lack of sincerity. It is this last that deprives Louis of any vestige of claim to be the “one true genius of jazz,” etc., etc.

Louis is still technically a great trumpet-player. But the greatest ever? Or, as so many of the Armstrong fans would have it, the only jazz trumpeter of any worth?

A bit far-fetched, you may think, but I have heard some Louis fans say that, and there are probably many more who have heard the same. Which, of course, wipes out at one fell swoop the late Bix Beiderbecke, Red Nichols, Henry Allen, Junr., Mugsy Spanier . . . (fill in according to taste). What supreme bias and bigotedness! In fact, how delightfully naïve!

[...]

All these stars have as much a place in the ranks of great jazz trumpeters as Louis. And as to calling Louis the greatest hot soloist--maybe these fanatical soloists have never heard of Venuti, Teagarden, Hawkins...but why continue?

Place In The Sun

No, Louis has a place, a very definite place, in the sphere of jazz--a place which is held more by his past performances than his recent. The Louis who gave us ‘Muggles,’ ‘Mahogany Hall Stomp,’ ‘Black and Blue,’ ‘Some of these Days,’ and others of the same standard, was an artist--even a great artist.

But the Louis who inflicted on us the ‘New Tiger Rag,’ ‘Snowball’ ‘That’s My Home,’ and the semi-comedy ‘High Society’ is inclined to become rather boring; except to those drunk with his very charming personality. And personality alone, alas, does not make genius."

Feather's columns in this period, even when knocking various Armstrong eras, clearly had respect for the trumpeter, who befriended young Feather in this period. The same could not be said for R. Edwin S. Hinchcliffe, who published "Hooey about Louis" in the Melody Maker on December 8, 1934:

"Perhaps no person in the whole world of jazz arouses such deep controversy as “Satchmo.” He is either reviled beyond reason, or deified beyond reason, and few people attempt to get a true perspective on his powers.

An article in a contemporary describes him as the genius of jazz; the greatest of all hot soloists. This is typical of the overstatements which his frenzied admirers are constantly letting loose about their idol, for, according to them, he is the most significant and outstanding figure in the world of jazz. How does this viewpoint stand when examined in a cold and analytical spirit?

To begin with, it places Louis on a higher level than one who has done at least as much as, if not more than, the Great Fun Man to raise jazz to its present position, where at last, however grudgingly, it is beginning to be recognized as a definite art form. I refer, of course, to Duke Ellington.

[...]

The facts must be faced. Up to two years ago, Louis was a genuine artist; there was a sincerity in his work, a genuine conviction in his playing. His stupendous high notes were used only when they were fitting, as logical steps in his constructions, to lend force to his meaning, and for building up climaxes. Then he began to decline from being Louis, the great artist, to Louis, the great personality-monger and the music-hall comedian.

Going Up On Top

Examining his later records, what do we find? A striving after unnecessary top-notes--not always too successfully reached; breaks that are exaggerated and in all too many cases, not particularly rhythmic. And, worst of all, a patent lack of sincerity. It is this last that deprives Louis of any vestige of claim to be the “one true genius of jazz,” etc., etc.

Louis is still technically a great trumpet-player. But the greatest ever? Or, as so many of the Armstrong fans would have it, the only jazz trumpeter of any worth?

A bit far-fetched, you may think, but I have heard some Louis fans say that, and there are probably many more who have heard the same. Which, of course, wipes out at one fell swoop the late Bix Beiderbecke, Red Nichols, Henry Allen, Junr., Mugsy Spanier . . . (fill in according to taste). What supreme bias and bigotedness! In fact, how delightfully naïve!

[...]

All these stars have as much a place in the ranks of great jazz trumpeters as Louis. And as to calling Louis the greatest hot soloist--maybe these fanatical soloists have never heard of Venuti, Teagarden, Hawkins...but why continue?

Place In The Sun

No, Louis has a place, a very definite place, in the sphere of jazz--a place which is held more by his past performances than his recent. The Louis who gave us ‘Muggles,’ ‘Mahogany Hall Stomp,’ ‘Black and Blue,’ ‘Some of these Days,’ and others of the same standard, was an artist--even a great artist.

But the Louis who inflicted on us the ‘New Tiger Rag,’ ‘Snowball’ ‘That’s My Home,’ and the semi-comedy ‘High Society’ is inclined to become rather boring; except to those drunk with his very charming personality. And personality alone, alas, does not make genius."

******************************

Back in

the States, John Hammond was getting more publicity for his writing on the

music, both past and present. In a February 1935 article, Hammond mentioned

Bessie Smith's "Reckless Blues" and wrote, "Accompanying is an

amazing organist, Fred Longshaw, and Louis Armstrong, who does some of the most

skillful obligato work ever recorded--in the old days before he had been

spoiled by cheap showmanship and exploiting managers. The record is of another

world entirely, enormously moving and truly original folk music." In May

1935, with "Swing" on the rise, Hammond contributed a column for the Brooklyn

Daily Eagle, "A Survey of Recent Jazz Recordings--With a Digression on

Native 'Swing.'" As part of his "digression," Hammond wrote,

"The downfall of Louis Armstrong as the supreme jazz artist is probably

the severest blow of all to the swing connoisseur. In the middle twenties Louis

had a naivete and sincerity which combined with a fantastic grasp of the

trumpet and a guttural voice, produced completely satisfying results.

Fortunately, Brunswick has just come across with an old Armstrong record, “King

of the Zulus” and “Lonesome Blues,” which has not been obtainable for many,

many years. They plan to reissue it with considerable fanfare as an example of

the greatest of his work. 'Lonesome Blues' is really a masterpiece of the only

authentic blues vocal choruses Louis ever recorded plus a few bars of matchless

trumpet playing. The other side is a wild and uncontrolled affair about a

'chittlin’ rag' in which some one indulges in West Indian jive and Louis blows

the strangest notes that ever came from his horn. Emphatically it is a record

that should be heard."

[Commentary:

it's hilarious that Hammond could rail against "cheap showmanship" in

one column, then praise the "West Indian jive" on "King of the

Zulus."]

Hammond

wrote the above columns when Armstrong was off the scene, nursing sore chops in

Chicago without any gigs in sight. But after hooking up with Joe Glaser,

Armstrong mounted his comeback, recording for Decca Records in October 1935.

Hammond wasn't impressed, writing in his column of "Recent Jazz

Recordings" that he only recommended, "Louis Armstrong’s singing, and

not his playing, in 'I’m in the Mood for Love.'" Leonard Feather was even

more despondent, writing in "A Survey of 1935 In Jazz" in The Era,

"On the other hand, Louis Armstrong has reached a stage where his

showmanship overpowers his musicianship, his new Decca recordings showing that

his greatest days are, alas!, over."

We have now come to the

Feather portion of the program as he spent the rest of the 1930s reviewing

Armstrong's Decca recordings for the Melody Maker, always under the

pseudonym, "Rophone." Here's a batch:

Review of

“Lyin’ To Myself.” “Eventide.” “Thankful.” “Swing That Music”:

“The first side is perhaps the least weak of those four, and the last is the weakest. All four present the worst features of Armstrong and his band. Neither record is worth your attention in this prolific month.”

“The first side is perhaps the least weak of those four, and the last is the weakest. All four present the worst features of Armstrong and his band. Neither record is worth your attention in this prolific month.”

Review of

"Dippermouth Blues" (3 stars) and "If We Never Meet Again"

(2 stars):

“The first side is mostly played by Jimmy Dorsey and His Orchestra, with a short contribution by Louis playing a variation of the identical solo created two decades ago by his mentor, king Oliver. On the reverse Louis has Luis Russell’s Band with him again, struggling through one of those doctored-up commercial arrangements in the usual manner.”

“The first side is mostly played by Jimmy Dorsey and His Orchestra, with a short contribution by Louis playing a variation of the identical solo created two decades ago by his mentor, king Oliver. On the reverse Louis has Luis Russell’s Band with him again, struggling through one of those doctored-up commercial arrangements in the usual manner.”

Review of

"On a Cocoanut Island" and "To You Sweetheart Aloha" (1

star each):

“Just play these two and then play ‘Muggles’ or ‘West End Blues’ or ‘Save It Pretty Mama.’ Then you’ll know just how tragic it is that Louis has descended to making records with a Hawaiian orchestra.”

“Just play these two and then play ‘Muggles’ or ‘West End Blues’ or ‘Save It Pretty Mama.’ Then you’ll know just how tragic it is that Louis has descended to making records with a Hawaiian orchestra.”

Review of

"Cuban Pete" and "She’s the Daughter of a Planter From

Havana":

“Poor Louis! My heart bleeds for him when I think of the recording moguls sitting round a conference table, deciding which titles will be the hardest and most unsuitable for him to do on his next session, and then making him go ahead and do them. I can only imagine that that is the way they work it, though I can’t see what good it does anyone.”

“Poor Louis! My heart bleeds for him when I think of the recording moguls sitting round a conference table, deciding which titles will be the hardest and most unsuitable for him to do on his next session, and then making him go ahead and do them. I can only imagine that that is the way they work it, though I can’t see what good it does anyone.”

Review

of "Yours and Mine" (3 stars) and "Public Melody Number

One" (2 stars):

“In his trumpet chorus in ‘Yours And Mine’ is a rare glimpse of the real Louis emerging ephemerally from the shroud of commercialism and offering a truly lovely performance in which he works up to a high-note ending which is logically placed, without the usual synthetic suspense. And what a superb note it is!

“In his trumpet chorus in ‘Yours And Mine’ is a rare glimpse of the real Louis emerging ephemerally from the shroud of commercialism and offering a truly lovely performance in which he works up to a high-note ending which is logically placed, without the usual synthetic suspense. And what a superb note it is!

It is

obvious that Russell’s band has improved considerably. There is now some sort

of tone in the ensemble and considerably more team spirit. Louis’ vocal is the

shadow of the old days; he still harps on the dominant, as if too weary to

introduce any real variations of the melody; and his gruffness seems to

have lost the personal warmth that used to qualify him as the world’s greatest

jazz singer. To-day it is just gruffness.

'Public

Melody Number One’ is a repetition of Louis’ infamously short and inadequate

appearance in the film ‘Artists and Models,’ dished up in the worst commercial

fashion with an appalling, gallery-courting finish.”

Review of

"Struttin'' With Some Barbecue" (4 stars):

“Good Armstrong discs being so rare nowadays, I have given this four stars; but if you have sentimental recollections of the original version of ‘Barbecue,’ which he waxed in 1928, or if you expect a background worthy of its leader, be prepared to adjust your standards.”

“Good Armstrong discs being so rare nowadays, I have given this four stars; but if you have sentimental recollections of the original version of ‘Barbecue,’ which he waxed in 1928, or if you expect a background worthy of its leader, be prepared to adjust your standards.”

Review of

"Sweet as a Song" and "Let That Be a Lesson to You" (1 star

each):

“Have you ever seen a racehorse pulling a milk cart?”

“Have you ever seen a racehorse pulling a milk cart?”

Review of

"Alexander's Ragtime Band" and "Red Cap" (2 stars each):

“An intro better suited to a newsreel; first chorus shockingly arranged with bleating first alto; vocal at the nadir of Louis’s ability; and a swell trumpet chorus--that’s all there is to ‘Alexander,’ in which the improvement I noted lately in Luis Russell’s band is no longer to be observed. ‘Red Cap’ is the latest addition to the series of sagas of lower-middle-class jobs for which ‘Shoeshine Boy’ started a vogue. It means pullman porter. Louis does nothing that he has not done ten times better in scores of earlier records.”

“An intro better suited to a newsreel; first chorus shockingly arranged with bleating first alto; vocal at the nadir of Louis’s ability; and a swell trumpet chorus--that’s all there is to ‘Alexander,’ in which the improvement I noted lately in Luis Russell’s band is no longer to be observed. ‘Red Cap’ is the latest addition to the series of sagas of lower-middle-class jobs for which ‘Shoeshine Boy’ started a vogue. It means pullman porter. Louis does nothing that he has not done ten times better in scores of earlier records.”

Review of

"I Double Dare You" and "True Confession" (1 star

each):

“The time has come for a showdown on this Armstrong band and the reason for its poor work on recent recordings in spite of a star personnel that might well be expected to turn in terrific work.

[...]

The limp work behind the opening vocal of ‘True Confession’ is a lifelike illustration of the band’s morale. Note also the very sentimental tenor and the alto which, though nice, is but a shadow of the old Holmes.

Louis, I double dare you to make something out of this band.”

Review of "On the Sentimental Side" and "It's Wonderful" (1 star each):

“If you are inclined to be a little on the sentimental side, you will wonder how the man who made ‘West End Blues’ and ‘Muggles’ and ‘Confessin’’ could lose even his sense of tempo and play this number just twice as fast as necessary.

There are the usual spots of welcome trumpet at the end of both sides, but the gross result is another couple of gross caricatures of the old Louis. “

“The time has come for a showdown on this Armstrong band and the reason for its poor work on recent recordings in spite of a star personnel that might well be expected to turn in terrific work.

[...]

The limp work behind the opening vocal of ‘True Confession’ is a lifelike illustration of the band’s morale. Note also the very sentimental tenor and the alto which, though nice, is but a shadow of the old Holmes.

Louis, I double dare you to make something out of this band.”

Review of "On the Sentimental Side" and "It's Wonderful" (1 star each):

“If you are inclined to be a little on the sentimental side, you will wonder how the man who made ‘West End Blues’ and ‘Muggles’ and ‘Confessin’’ could lose even his sense of tempo and play this number just twice as fast as necessary.

There are the usual spots of welcome trumpet at the end of both sides, but the gross result is another couple of gross caricatures of the old Louis. “

******************************

All of the above reviews

appeared in England, but by this point, Down Beat was off and running,

covering the scene in the U.S. Armstrong quickly took his place in their

crosshairs, especially in reviews by young George Frazier. "ARMSTRONG IS

PLAYING COMMERCIAL ‘JUNK’” ran a front-page headline in March 1936. “Louis

Armstrong’s playing at the Metropolitan Theatre here in town this week,”

Frazier reported. “From the swing angle, it’s really a bringdown show, giving

Louis no opportunity to do anything but mug and play pure commercial junk. He

sings ‘Shoe Shine Boy,’ ‘Old Man Mose,’ and ‘I Hope Gabriel Likes My Music,’

which should give you a faint idea of the Rockwell-O’Keefe influence.”

In May 1936, Armstrong

closed the famous "Swing Concert" at the Imperial Theatre, getting

great notices in the black press and in the general music press. But Hammond

wasn't pleased, writing in Down Beat “Novelty was the keynote of the

evening” and “The audience, whose musical sensibilities were about as deep as a

song-plugger’s, lapped it all up.” Of Armstrong, Hammond said, “Louis

Armstrong’s band could not conceivably have been less suited to its leader’s

genius.” Hammond might have referred to Armstrong’s “genius” but his writing

had featured almost entirely anti-Armstrong commentary and he would not let up

in the ensuing decades. When the Decca “Mahogany Hall Stomp” was released,

Hammond wrote that Armstrong “committed the unpardonable sin of sullying the

memory of his Okeh release of Mahogany hall Stomp first by a poor Victor

record...and now by a godawful Decca effort utilizing the present Luis Russell

bunch. All the old verve and invention are gone; in their place stodgy,

unexciting virtuosity by a self-conscious soloist.”

Down Beat also sent

Frazier to review the Imperial concert, using another subtle headline,

"SATCHLMO'S BAND IS WORLD'S WORST." "...Louis Armstrong went on

closing--which was too sad," Frazier wrote. "Louis, by the way,

played like a virtuoso and did nothing to disprove my commentary on his job at

the Metropolitan in Boston. That band of his is just about the world’s worst.”

During this period, Down Beat was running a reader’s poll to name an

“All-Time Swing band.” Given Down Beat’s coverage of white artists--and

it’s patronizing, sometimes downright racist cartoons about black musicians--it

wasn’t a surprise that the leading vote getters were all white, with Tommy

Dorsey and Gene Krupa amassing the most votes. "Louie’s recent commercial

playing has hurt him with swing fans, many either voting for the ‘old Louie’ or

giving their preference to [Roy] Eldredge or Bunny Berigan,” the accompanying

article stated. In the end, Armstrong came in second to deceased

trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke and his band amassed only 38 votes in the "Swing

Band" category (Benny Goodman won with 3,534). This pattern continued

throughout the rest of the 1930s, Armstrong eventually settling into fourth

place in the trumpet category by 1939.

The other major publication

covering the jazz scene in the United States was Metronome. In March

1940, young Barry Ulanov reviewed a live performance of Armstrong's big band.

Here are some extended excerpts:

"If the band has a style, it is chiefly one

of playing without discipline or musical organization. And yet, there are some

of the greatest hot musicians extant in this Louis Armstrong band. Upon

occasion they stand out. For the most part, it is a matter of uneven,

uninspired, undistinguished playing of similarly afflicted

arrangements."

[...]

Very rarely, indeed, are the soloists, except for Louis himself, allowed to get off anything resembling an improvised solo. Even Louis is limited to spectacular blasting and monotonous one-note repetitions which suggest nothing so much as a circus entertainer.

From all of his, you may gather that I was much disappointed in Louis Armstrong’s Orchestra. You are right. For it is a disgrace to the art, and even to the commerce, of jazz, that so many fine people should be buried in such musical desolation, so that, as one of them said to me, “Man, we don’t get a chance to really play no more!”

[...]

Louis Armstrong’s solos, as I noted above, are more spectacle and blast than fine music. But every once in a while you hear a spark of the old Louis -- pretty, big tone, lovely melodic ideas and a wealth of genuine feeling. And that is reason enough to listen to this shapeless band.

Vocals: Louis’ famous gruff vocals seem to have brought on a laryngital approach to singing that takes all the joy and amusement out of his hitherto delightful warbling.

[...]

Last Words: Enough said!"

[...]

Very rarely, indeed, are the soloists, except for Louis himself, allowed to get off anything resembling an improvised solo. Even Louis is limited to spectacular blasting and monotonous one-note repetitions which suggest nothing so much as a circus entertainer.

From all of his, you may gather that I was much disappointed in Louis Armstrong’s Orchestra. You are right. For it is a disgrace to the art, and even to the commerce, of jazz, that so many fine people should be buried in such musical desolation, so that, as one of them said to me, “Man, we don’t get a chance to really play no more!”

[...]

Louis Armstrong’s solos, as I noted above, are more spectacle and blast than fine music. But every once in a while you hear a spark of the old Louis -- pretty, big tone, lovely melodic ideas and a wealth of genuine feeling. And that is reason enough to listen to this shapeless band.

Vocals: Louis’ famous gruff vocals seem to have brought on a laryngital approach to singing that takes all the joy and amusement out of his hitherto delightful warbling.

[...]

Last Words: Enough said!"

******************************

By 1941, Armstrong’s 1920s recordings were being reissued by Columbia, which set into motion a whole new series of criticisms that Armstrong had hit his peak in 1928 and was now out of gas (it took everyone about seven years to catch up with Feather and Hammond). This article from Paul Eduard Miller in the January 1941 issue of Music and Rhythm--titled “Musical Blasphemies”--is a particularly forceful example:

By 1941, Armstrong’s 1920s recordings were being reissued by Columbia, which set into motion a whole new series of criticisms that Armstrong had hit his peak in 1928 and was now out of gas (it took everyone about seven years to catch up with Feather and Hammond). This article from Paul Eduard Miller in the January 1941 issue of Music and Rhythm--titled “Musical Blasphemies”--is a particularly forceful example:

"Armstrong no longer is a vital force in hot jazz. His influence on other players, admittedly a widespread influence, has pretty much petered out. He has accomplished nothing as creatively and artistically eloquent as West End Blues (1927). His “improvisations” today display none of the sparkle and genuineness of his 100 or more accompaniments for blues singers, and his performances on the approximately 64 sides by his own small group for the Okeh label.

Creatively and artistically, Armstrong is dead. Only the performance of really good music can again make his voice heard forcefully.

Exactly 18 years after his first junket to the Windy City to join King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, at the age of 41, again came to Chicago to lead and play with his own orchestra.

The Armstrong face had matured, and the excitement of playing no longer disturbed him. Presumably he was a wealthy man. Certainly he was a famous one. His picture had been printed in countless magazines and newspapers, and his technical virtuosity had been the subject of high praise by critics, hot jazz vans, college professors and musicians both academic and practical, classical and popular. The praise had come from Europe, from Australia, from Canada, from South America, as well as the United states.

The Armstrong playing had matured too. It was completely confident; it never hesitated, never groped for ideas, or for musical phrases to express those ideas. But with this maturing came other things as well. Armstrong’s showmanship improved, but sadly enough, it improved so much that it became an outright commercial attitude. His forehead was dotted with beads of sweat as he reached for high C. Gradually he substituted these meaningless pyrotechnics for the more sober, more sincere performances of the days of the Armstrong Hot Five. Armstrong had chosen to play exclusively for the box-office.

Armstrong’s justly deserved fame as a great virtuoso of the trumpet is not to be denied. But the time had come for the hot fan and critic to ask himself: What is the purpose, the goal, of a technically skilled instrumentalist who understands his medium and can thus eloquently and feelingly express the music of that medium?

Is it merely to attempt laboriously to pump into the meagre musical material of a popular song meanings which are not there? Assuredly not. Therein lies Armstrong’s failure."

******************************

Such

reviews came hot on the heels of the publication of Jazzmen in 1939 and

the rediscovery of trumpeter Bunk Johnson. As interest in early New Orleans

jazz grew, some critics, Leonard Feather especially, fought the trend.

“Harmonically, both the arrangers and the soloists have broadened their horizon

amazingly,” Feather wrote in December 1943. “The hot man who in 1929 might have

been scared to insert an extra chord suggestion or dissonance, brings so many

advanced effects into his improvisations in 1943 that the old-time soloists in

many instances sound utterly naïve. As an example of this, compare Art Tatum or

King Cole or Mel Powell with an old-time pianist like Art Hodes or Jelly Roll

Morton. It seems almost fantastic that the differences can be so vast with the

passage of less than a generation. They are the differences between a master of

oratory and a child just learning to talk. This progress in the subtleties of

hot playing is one of the most potent arguments against clinging to one’s old

beliefs in the heroes of the past."

Just a

few weeks after writing that, Feather was present at the first Esquire

“All-American Jazz Concert” at the Metropolitan Opera House. Again, this

concert takes up about half a chapter in my book and I don’t want to rehash it

here but it’s worth mentioning that the harshest reviews towards Armstrong came

from Feather and Ulanov, both now champions of “progressive” jazz. Here’s some

excerpts from Ulanov in Metronome:

"There were several obvious causes for the

frigidity and lack of motion of most of the evening. Louis and Teagarden were

out of place; neither by style nor technique were they fitted to play with Roy

and Hawk and Tatum. Barney Bigard didn’t seem altogether at ease either, but

that certainly wasn’t because of any musical deficiency.

[...]

Next year, if this concert is given again, let’s hope we’ll be spared the pathetic spectacle of a giant of the past, like Louis, hopelessly trying to play with his younger betters. Perhaps we’ll get someone like Cootie Williams in his stead. Maybe modern musicians, and leaders, like Lionel Hampton and Roy Eldridge and Coleman Hawkins will be allowed to take over. Then we’ll really get the great music this gathering of the great presaged but only briefly presented."

[...]

Next year, if this concert is given again, let’s hope we’ll be spared the pathetic spectacle of a giant of the past, like Louis, hopelessly trying to play with his younger betters. Perhaps we’ll get someone like Cootie Williams in his stead. Maybe modern musicians, and leaders, like Lionel Hampton and Roy Eldridge and Coleman Hawkins will be allowed to take over. Then we’ll really get the great music this gathering of the great presaged but only briefly presented."

And here’s a taste of Feather in Melody Maker:

"An aggregation of talent like this could hardly

fail to produce some exciting music. Although the rehearsals were short and

hectic and the musicians felt they would have done better if they’d had more

time to prepare the show together, the fact is that only three things,

fundamentally, were wrong with the concert and everything else was wonderful.

THREE WRONG THINGS

The three wrong things were Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden and the audience. Louis’s performance was pathetic. I had voted for him myself in the pool, but after hearing his performance, I had to remind myself again that sentiment should never influence critical opinion.

Louis is simply getting old and hasn’t got the power, the imagination or the lip to keep up with the younger stars who have built on the foundations he set so many years ago and have since gone far ahead of him.

His singing, because it required less physical effort, was fine. But not on one number at the trumpet did he dispel that awful uneasiness that kept me wondering all the time whether the next note was going to be a good one or a clinker. It wasn’t just the clinkers, though; it was the lack of inspiration.

And you couldn’t excuse him on the basis of surroundings, because the same thing happened at rehearsals, on a previous broadcast and everywhere else. Louis was hopelessly outclassed by Roy Eldridge, whose playing inspired the whole band. The other musicians talking about it afterwards, all felt the same way about Armstrong.

Jack Teagarden played a few good solos, but his vocal qualities have almost disappeared, and altogether he seemed ill at ease and out of place in this combination. With Higgy or Lawrence Brown in this chair, and with Roy unencumbered by Louis, this jam band would have been just about perfect.

The third fault, the audience, caused such displays as the long drum solo by Catlett which ruined the end of Bigard’s great job on “Tea for Two.” It was a stupid, undiscerning audience, which reacting to showmanship instead of musicianship.

[...]

I don’t like jazz in opera houses and concert halls, but if that’s the only way to bring musicians of this caliber together, it’s worth doing. All I hope is that next year we won’t hear Louis’s pathetic efforts to get the release of “Stomping at the Savoy”--he couldn’t even get those chord changes--and that next year’s band will be elected on the basis of current performance instead of past achievement.

That will only necessitate two changes in the line-up, but they’re very important changes."

THREE WRONG THINGS

The three wrong things were Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden and the audience. Louis’s performance was pathetic. I had voted for him myself in the pool, but after hearing his performance, I had to remind myself again that sentiment should never influence critical opinion.

Louis is simply getting old and hasn’t got the power, the imagination or the lip to keep up with the younger stars who have built on the foundations he set so many years ago and have since gone far ahead of him.

His singing, because it required less physical effort, was fine. But not on one number at the trumpet did he dispel that awful uneasiness that kept me wondering all the time whether the next note was going to be a good one or a clinker. It wasn’t just the clinkers, though; it was the lack of inspiration.

And you couldn’t excuse him on the basis of surroundings, because the same thing happened at rehearsals, on a previous broadcast and everywhere else. Louis was hopelessly outclassed by Roy Eldridge, whose playing inspired the whole band. The other musicians talking about it afterwards, all felt the same way about Armstrong.

Jack Teagarden played a few good solos, but his vocal qualities have almost disappeared, and altogether he seemed ill at ease and out of place in this combination. With Higgy or Lawrence Brown in this chair, and with Roy unencumbered by Louis, this jam band would have been just about perfect.

The third fault, the audience, caused such displays as the long drum solo by Catlett which ruined the end of Bigard’s great job on “Tea for Two.” It was a stupid, undiscerning audience, which reacting to showmanship instead of musicianship.

[...]

I don’t like jazz in opera houses and concert halls, but if that’s the only way to bring musicians of this caliber together, it’s worth doing. All I hope is that next year we won’t hear Louis’s pathetic efforts to get the release of “Stomping at the Savoy”--he couldn’t even get those chord changes--and that next year’s band will be elected on the basis of current performance instead of past achievement.

That will only necessitate two changes in the line-up, but they’re very important changes."

******************************

Feather’s

column drew some backlash, with “Detector” in the Melody Maker writing a

response after hearing Armstrong play on a radio broadcast with his big band.

“The notes came out as clear and as spontaneously as ever in the past,”

“Detector” wrote. To break up the negativity, here is the rest of this defense:

"It was still the same grand old Satchmo,

especially in ‘Lazy River.’ But perhaps that is what was worrying Leonard

Feather. New young players spring up with new ideas while Louis remains just

Louis….Practically everything he did he himself originated, and the fact that

no one else has appeared on the scene who has invented even a tenth of what

Louis invented proves that he was the greatest creative artist jazz has ever

known. Secondly, Louis’s playing is not only one of the very few things in jazz

that have not dated, but because of its undeniable artistry probably never will

date as long as jazz remains in existence, so what need is there for him to attempt

to change it? There are many clever new trumpet players in the limelight

to-day, and many of them have originated tricks and styles of their own.

If Leonard Feather had left it at saying they have built on the foundations

Louis laid I would have had no quarrel with him. But when he goes on to say

that they have gone far ahead of Louis I can only just wonder which way

“ahead” is supposed to be."

******************************

Naturally, not everyone

felt that way when listening to Louis’s big band. George T. Simon heard a

broadcast at the Zanzibar in December 1944 and wrote in Metronome, “I’ve

heard several of them and never in my life have I heard anything that does

anyone a greater injustice. The choice of tunes, many of the arrangements, the

pacing of the shows, and, in many instances, the band behind him are positively

abominable. Nothing could possibly do more harm to such a great artist. It’s

absolutely murderous. If Louis can’t be presented to the radio public in a

better light that that, he shouldn’t be presented at all. I sincerely hope that

by the time this gets into print somebody will have give this subject some

thought and rectified the ridiculous conditions, or else that Louis will be

spared future embarrassment and the rest of his broadcasts be cancelled.”

******************************

In 1945, the “Jazz Wars”

heated up. As discussed in my book, Feather and Ulanov went to Armstrong’s home

to interview him in March and were shocked when he criticized those who wanted

to stick to playing jazz like in the old days. In turn, they devoted the

following month’s Metronome to him and praised him up and down, even

going back on their original views about the Esquire concert.

Feather and Ulanov were now openly at war with the traditional jazz disciples, now known as “moldy figs.” In The Record Changer, the bible of New Orleans jazz, Rudi Blesh wrote in March 1945, “Jazz is a fine art and therefore a subject that concerns everyone, and therefore an activity too large and important to be dominated or directed by a few individuals. Should there exist within Jazz a small clique or hierarchy devoted to such an idea, it would be at once as harmful and much more dangerous than the Goffin-Feather-Ulanov triarchy which are at least openly on the other side of the fence.”

Feather and Ulanov were now openly at war with the traditional jazz disciples, now known as “moldy figs.” In The Record Changer, the bible of New Orleans jazz, Rudi Blesh wrote in March 1945, “Jazz is a fine art and therefore a subject that concerns everyone, and therefore an activity too large and important to be dominated or directed by a few individuals. Should there exist within Jazz a small clique or hierarchy devoted to such an idea, it would be at once as harmful and much more dangerous than the Goffin-Feather-Ulanov triarchy which are at least openly on the other side of the fence.”

The following year, Blesh

did his part for those on his side of the fence by publishing a history of

jazz, Shining Trumpets. Up to this point, I have only dealt with

magazines and newspaper articles but here, for the first time, was the “tragedy

of Louis Armstrong” in a major book. If you haven’t read it--you can find it on

Archive.org--here’s a long excerpt from Blesh’s Armstrong chapter:

"Speak of jazz to a group and three out of four people will think of Louis Armstrong. The trumpet, leader of the polyphony, and its player come naturally--if not quite justly--to stand for the music. The public, which likes and no doubt needs to personify whole movements and eras of human activity in single figures, naturally finds the triumvirate of New Orleans horns too complex and depersonalized a figure. Yet on this triumvirate--if not, indeed on the whole band--should such a symbolic designation fall. So, from the earliest days of record, New Orleans crowned its trumpeters as Kings; in the fine cooperative days of true jazz such bestowals carried the weight of a dignity and an honor in which the entire band shared.

"Louis Armstrong inherited naturally the honors relinquished in turn by Bolden and Keppard, took the scepter from King Oliver’s failing hand. Bunk Johnson was in an eclipse that bade fair to be permanent.

"Had Armstrong understood his responsibility as clearly as he perceived his own growing artistic power--had his individual genius been deeply integrated with that of the music, and thus ultimately with the destiny, of his race--designated leadership would have been just. Achievement is not without responsibility ; progress is not always what it seems; the revolutionary must himself be judged by the fruits of his revolution.

"Around Louis clustered growing public cognizance of hot music and those commercial forces, equally strong and more persistent, which utilize the musical communication system of the phonograph record, the then new radio and talking motion picture, and the printed sheets of the Tin Pan Alley tunesmiths. And behind this new symbolic figure was aligned the overwhelming and immemorial need of his own race to find a Moses to lead it out of Egypt.

[...]

"One criticizes the results of Louis Armstrong’s fine work with the greatest reluctance, indeed sadly, because, more than a man of true personal charm, he is one of personal artistic integrity. His grasp of what jazz means, the sort of group effort which it must represent, unfortunately failed to match his genius. For, ironically, any of Louis' solos, executed as they are in front of a large swing band as before a tinseled backdrop, are a part of pure and authentic jazz that could be translated bodily, note for note, into the context of the small band polyphony. Louis was--and remains--an ineffably hot individual creator. But the trumpet is not jazz; it is only the leading voice of the polyphony and an occasional soloist; the lead, by its nature, can be transferred to harmonized large band swing, where the inner voices of clarinet and trombone cannot.

"It is therefore no wonder that the public, dazzled by Armstrong's true brilliance, was fooled; that to this day swing is considered to be that which it is not--a development from, and of, jazz. Swing borrows two qualities from jazz : hot accent and characteristic timbres. The average listener does not go deeply into musical structure; even in listening to pure jazz he is likely to concentrate only on the trumpet as, in watching football, he sees only the man carrying the ball. Even today, with swing deep in the narrowing walls of its blind alley, the public thinks that it is jazz which has reached its senility!

"The crucial point is that Louis Armstrong himself was fooled; however misled, his sincerity cannot fairly be brought into question. Armstrong did not invent the large band. As a tendency, it has existed parallel with jazz almost from its beginnings. His seemingly revolutionary act was that he appeared to effect an amalgamation of jazz with the large-band form; this hybrid is what is known as swing. It was not obvious to him-- or, for that matter, to scarcely anyone else--that everything vital in jazz was left out in a sterile crossing. Jazz itself is revolutionary: Armstrong's act was that of counter-revolution.

"Ellington's later act, the crossing of swing with the music of various European composers, is a further countermove that seems abortive enough now but may, ironically enough, complete the process of de-Africanization so that the large band will lose its last vestiges of hotness and African accent to become a variety of music thoroughly and solely in the western tradition. Such an end development, regardless of its musical value, might help to clear away the clouds of confusion which now obscure the subject. Nevertheless, revolutionary or counter- revolutionary, Armstrong, like Ellington, must be judged in the end by the value of what he has done.

"Ferdinand Morton was the rare individual who combined two functions in his work. He completed an entire period of jazz and marked the pathway the future should take. He was personally identified with the whole development of the music to a degree that seldom happens in any art. When Jelly Roll said that all the jazz styles are "Jelly Roll Style,” his words are, if obviously not actually true, at least symbolically so. It is a wholly remarkable indication of the scope, insight, and great-ness of the man, that Morton, a powerful individualist if there ever was one, could be so thoroughly imbued with the principle of group creation as to direct a great part of his activity into it. We find his greatest qualities as an individual creative artist not in his solos but in his work with, and as a part of, the group.

"Louis Armstrong, an equally powerful creator, falls, on the contrary, into the category of the individualist. Although in has early phases he joined with the collective group playing improvised polyphony, obviously feeling in those years the stimulus and incomparable satisfaction from so doing, lent to that group new and powerful characteristics and might, in common with Morton, have contributed vastly to its continued logical development, he chose, nevertheless, and chose unfortunately, another course. At a time when the whole development of hot music was at a crisis, he directed his vast creative power toward the growing big-band swing that is opposed to jazz.

"Events robbed Morton in his later years of the opportunity to serve the music of his race; Armstrong had the opportunity and threw it away. So, although all of Louis Armstrong's work is impressive, even in relation to all music, that from his mature period is in a field hostile to jazz and, it may be believed, to his own truest expression.

"Had Armstrong chosen to develop polyphonic jazz, together with the utmost employment of the solo within, and in just relation to the polyphonic framework, this would have necessitated working with the greatest of the other instrumentalists. It would have meant a continued and continuous association with Ory, St. Cyr, and the Dodds brothers; it would have meant working ultimately--as he never did--with Jelly Roll Morton. But this is to speak of what might have been. Armstrong's path led him elsewhere and herein lies not merely a serious blow to art but the tragedy of Louis Armstrong, the artist."

******************************

Blesh

also wrote, “Louis Armstrong could conceivably return to jazz tomorrow; he did

it once before, from 1925 to 1928, when he left Henderson and returned to

Chicago to record.” Armstrong did indeed “return to jazz” in the eyes of folks

like Blesh in 1947 by breaking up the big band and forming the small group All

Stars. In the September 1947 Record Changer, editor Nesuhi Ertegun

wrote, “By the time this issue of the Changer reaches you, Louis

Armstrong will be leading a seven-piece band at Billy Berg’s here in Hollywood.

I don’t know who else will be in the band, and frankly I don’t care much. As

long as Louis plays at Berg’s, the editorial office of the Changer will

be transplanted there and we will be in much too mellow a mood to be

campaigning against the bad sides of the jazz scene. That’s why this piece had

to be written now. As soon as Louis starts blowing everything in the world is

bound to look wonderful.”

Indeed,

the formation of the All Stars seemed to be greeted with unanimous praise at

first. “Louis Armstrong had forsaken the ways of Mammon and come back to jazz,”

Time magazine famously opened its September 1 column. But any goodwill

was gone by the end of the same article when Armstrong got his first digs in at

bebop. 'Take them re-bop boys,” he said. “They're great technicians.

Mistakes--that's all re-bop is. Man, you've gotta be a technician to know when

you make 'em. ... New York and 52nd Street--that's what messed up jazz. Them

cats play too much music--a whole lot of notes, weird notes. . . . That don't

mean nothing.”

Armstrong

had survived the “Jazz Wars” between the critics in the mid-40s but now he was

in the front line in the “Jazz Wars” between musicians. “Modern” musicians

lined up to take their shots at not just Armstrong but more broadly, the

musicians of his generation. Naturally, Leonard Feather was happy to give them

a big platform with his “Blindfold Test” series in Metronome. “These

oldtime musicians and fans romanticize themselves into a false conception of

how things were played years ago,” Dave Tough said in the December 1946

installment, blasting Kid Rena’s Jazz Band of New Orleans with the caveat, “All

the same, these musicians are less ridiculous than the fans who idolize them.

How can they be sincere? It’s just one of those esoteric cults.” “I think it’s

a bad idea for kids or youngsters who are interested in music to pick up on

Dixieland; everyone should try to progress,” Mary Lou Williams said in the

September 1946 installment after beating up Feather targets Johnson and Art

Hodes. Feather played Coleman Hawkins his 1925 recording of “Money Blues” with

Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson and Hawkins said, “I’m ashamed of it,” gave it

“No stars” and said, “It’s an amazing thing, there are kids 22, 23 years old

who get hold of these records and they don’t think anything has ever been made

that’s better than that sort of thing and never will be. I don’t understand it!

To me, it’s like a man thinking back to when he couldn’t walk, he had to

crawl.” Hawkins concluded, “That’s amazing to me, that so many people in music

won’t accept progress. It’s the only field where advancement meets so much

opposition.” Even with the “moldier” Mezz Mezzrow--who gave “Congo Blues” with

Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker “no stars” and said, “If that’s music, I’ll

eat it”--Feather played him a record by Johnson and elicited this response: “Is

that one of Bunk Johnson’s abortions?”

In Dizzy

Gillespie’s installment, he said of a record by Bechet and Mezzrow, “That must

have been made in 1900….No harmonic structure here; two beats; bad rhythm,

nothing happening; just utter simplicity, but how simple can you get? You can

get a little boy eight years old to play that simple.” Played a Wild Bill

Davison record with Eddie Condon, Gillespie said, “Reminds me of carnival days.

When I ran away from school and wanted to join the carnival. But this isn’t

even a good modern carnival….Condon in there with his mandolin. No

stars, no nothing.”

Finally,

Feather played two Armstrong performances for Gillespie, “Savoy Blues” from

1927 and “Linger in My Arms a Little Longer” from 1946. Of the Hot Five

classic, Gillespie allowed, “Louis always sounds good to me--he might

not have the chops he used to have, but his ideas are always fine.” He then

admitted, “No, I wasn’t influenced by him because I’d never heard his records.”

He gave it “One star,” saying, “I only like Louis on this.” For “Linger in My

Arms,” Gillespie said, “Louis shouldn’t play a solo with a straight mute--it

only sounds good with a section...I prefer to hear him play legato...the tune

holds him down here; it’s a wasted effort. Vocal is wonderful. No voice, but

lots of feeling. I’d buy this just to hear Louis’s voice.” On the surface,

there are plenty of complimentary phrases--”Louis always sounds good to

me,” “Vocal is wonderful”--but there’s just as many backhanded comments: “He

might not have the chops he used to have,” “No, I wasn’t influenced by him,”

“No voice,” “It’s a wasted effort,” “One star.”

Critics

had been taking shots at Armstrong for years, but musicians did not, something

mentioned by Ullman in his review of my book. That changed in the late 1940s.

Dizzy became the most vocal critic, calling Armstrong a “plantation character”

in Down Beat in 1949, the same year he gave the story of the birth of

bebop to the Philadelphia Tribune: “Man, that was fun. A couple of us

who hated straight jazz used to get together at Minton’s playhouse in New York

and blow our brains out. We couldn’t take any more of that New Orleans music.

That was Uncle Tom music. It was for kids and birds. We simply had to get away

from that!” Others who publicly disagreed with Armstrong’s takes on modern jazz

included Stan Kenton and Woody Herman.

Musicians

aside, critics of all backgrounds sharpened their knives when the All Stars hit

the stand in the late 1940s. What follows is the tip of the iceberg.

British

writer Hugh Rees’s “Let’s Take Stock of Armstrong,” written after hearing

Armstrong at the Nice Jazz Festival in February 1948:

"It seems high time for a reassessment of Louis

Armstrong's importance. If we can forget the sentimental attachment which we

all have for the good old 'bad old days,' how does Armstrong's contribution to

the world's entertainment of the 1920s strike us today? Fortunately, many

records survive for us to refer to. And almost without exception they are

rough, without 'beat,' ill-formed and lacking the technical competence of, let

us say, Jean Goldkette's Orchestra. Certainly Louis himself showed signs even

then of the showmanship which was to make him a box-office draw in the

'thirties. But the rest of his recording combination (the vaunted 'Hot Five')

were no more than musical illiterates, unaware it seems of their own

incompetence. Nor was Louis without his faults. For all the charm and hard work

which he put into his playing there were all too many fluffed notes, rushed

phrases and embarrassing silence when the great man just didn't make it at all.

It was fortunate for Armstrong that, around 1929, he was taken up by a commercially-minded manager. Louis is a natural showman, an adequate if unimaginative trumpeter and an original if sometimes incomprehensible vocalist. Negro artists are frequently at an advantage over their white competitors (so long as they remain on stage!) and Louis' pigmentation together with his charming personality undoubtedly justified his manager's hopes. And though lacking the surprises of Ellington, the technique of Benny Goodman or the swing of Fats Waller, some of his records of those days succeeded in capturing that charm to an astonishing degree. But a truly great artist can never be satisfied with his achievements. Were Armstrong, as M. Panassie would tell us, 'one of the greatest musicians that humanity has known,' he would have developed. Instead, his approach has remained the same. His technique in a world of Gillespies, Hawkins, and Tatums seems childish. Every phrase that he uses he's used a hundred times before so that now they all sound faded.... After hearing that sad little broadcast from Nice one must face the truth. Louis Armstrong is a bore, whose manner of telling the old, old story has not improved in the least after twenty-odd years of repetition!"