Louis Armstrong, Joe Glaser and "Satchmo at the Waldorf"

On June 6, 1969, Louis Armstrong's longtime manager Joe Glaser passed away at Beth Israel Hospital in New York. On June 6, 2015, Terry

Teachout's play Satchmo at the Waldorf will be performed at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. Glaser's death will be discussed onstage tonight and each succeeding night of this sold-out run, just as it has been discussed since opening in 2012 and how it will be discussed in Chicago, San Francisco and more such venues into the future. Aside from the stage, it will also be discussed by theatergoers afterwards, who might have trouble separating fact from fiction. This blog will be my attempt to answer some of the questions that have arisen because of the play.

I saw Satchmo at the Waldorf twice when it was playing in New York in 2014 but

have never publicly commented on it; I'm not a critic. Since it opened, a great number of people have asked me the same question over and over again: "Is it

true?" I have always answered, "No, it's not," and offered my

supporting arguments but I never felt it was anything I needed to go public

with.

Why? Well, for

one thing, I think Terry would agree that’s not entirely true; in the program,

it clearly states that Satchmo at the Waldorf is a "work of fiction

based freely on fact." Last year, he told the Wall Street Journal, “The difference between writing a biography

and a play about the same subject is you don’t have to tell the truth in the

play. In Pops, I could only speculate. In Satchmo [at the

Waldorf] I could imagine things and create them myself. It was liberating.”

Yet it seems to me that just about everyone who sees it, takes it as the gospel

truth. This is a problem.

In full

disclosure, I consider Terry a friend and colleague, I enjoyed his book Pops

very much (my glowing review of it in the San Francisco Chronicle is

on his paperback jacket), he has always supported my various Armstrong-related

endeavors and he was helpful in getting my book published. I admire him tremendously. On top of that, the

actor in the one-man play, John Douglas Thompson, put in multiple sessions at the

Armstrong Archives where I work. He was the sweetest guy imaginable and really

did his homework. It shows on the stage; he deserves every accolade you've

probably heard.

But the play

contains a bit of a twist at the end that I have never bought (this whole blog will be filled with

SPOILERS so you might want to stop reading now if you haven't seen it!). And unfortunately, that twist—“fictional” warnings be

damned—has now become an accepted part of the Armstrong narrative. After

opening in Los Angeles last week, Terry gave an interview for KPCC in which he

tackled some of the questions the play addresses: "What was the exact

nature of the relationship between Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his manager? Why

did Armstrong feel at the end of his life that Glaser had sold him out? Why did

Glaser do the things that led Armstrong to feel that he had been betrayed?"

In its review, the Hollywood Reporter stated as fact, "After making a fortune off

the musician, Glaser died and left him nothing in his will. It’s a conflict

that strikes at the heart of Armstrong’s relationship with white people....When

he learns of Glaser’s will, it can only make him wonder if he’d been a fool to

trust the white man." Earlier this week, I did an interview for the New

York Post and when it was over, the reporter asked if I had seen Satchmo

at the Waldorf and if it was true that Armstrong "died broke." I

went into my defense case and she thanked me, saying she was "so

relieved" because the play had left her feeling that Armstrong had no

money at the end of his life.

This

is something we've been dealing with at the Louis Armstrong House Museum since Satchmo

at the Waldorf opened up: people going to see the play, then coming out to

the Armstrong House in Queens and pumping our docents full of questions:

"Was he exploited?" "Did he die broke?" "Is that why

he had to keep performing?" Sometimes the questions arrive as statements:

"I saw the Terry Teachout play. What a tragic ending Louis

had."

Where

does this all come from? One source and it is one Terry and I disagree on. He's

made his case clear in his biography and in his play but now I'd like to do the

same today, the anniversary of Joe Glaser's passing in 1969. I have dug deep

through the Armstrong Archives, listened to tapes, analyzed wills and estates,

and interviewed people who were alive at the time to present what I hope will be a more accurate portrait of not just Louis Armstrong's financial standing at

the end of his life (he did not die broke) but more importantly, a

thorough examination of how Armstrong truly felt about Glaser after Glaser died.

First,

a little backstory on the Armstrong-Glaser relationship, which was complex.

Both my book and Terry's book have lots about it (that we agree on!) so I

suggest seeking out those for more information. Many people would probably sum

it up this way: former gangster Joe Glaser takes over Louis Armstrong's career

in 1935, builds Associated Booking Corporation off of his talents and gets

wealthy beyond his wildest dreams while working poor Louis to death. Louis,

afraid to speak up to the tough white boss, keeps working like the devil as his

health fails. Glaser dies as a millionaire in 1969, leaves Louis nothing and

Louis has to continue working, bitter about how he was fooled into trusting

Glaser. The end.

This

is wrong on many levels. For one thing, it's too easy to measure the Armstrong-Glaser

relationship in dollars and cents. From 1935 to 1969, Joe Glaser took care of every aspect

of Armstrong's life, not just salary: finding gigs, publicity, hiring

musicians, firing musicians, paying taxes and on top of that, paying for

everything imaginable that Louis asked for: cars for friends, remodeling for

his house, sometimes money just for the sake of needing more money. Glaser even

paid the alimony of various All Stars band members such as Jack Teagarden and

Trummy Young.

Like

I said, my book is full of such stories, but here's a few more quotes that

didn't make it in from the private tapes, especially one featuring a

conversation with friends from 1951. In it, Louis brags about Glaser’s respect

for him: "Nobody—Bill Robinson, since Bill Robinson, nobody gets billed

over Louis Armstrong. You’ve got to be a big sonbitch,

boy. You’ve got to be the President of the United States before Joe

Glaser stands for it. That’s the kind of manager I

have. Regardless of his traits and all, he watch that spot."

"Regardless of his traits." Armstrong did not allow

anyone to criticize Glaser in his presence but he also knew that Glaser wasn't

infallible. His nickname for his manager was "Nervous Charlie" for

how he could overreact to things. For that reason, Armstrong and Glaser never

"hung out" together, as Satchmo

at the Waldorf makes clear, but they did check in every day and write

letters to each other constantly. Armstrong always referred to him as his “best

friend.”

More from the 1951 tape, showing that Armstrong was proud of

Glaser's gangster background: "That’s why I told Joe, I said, ‘Listen,

man, you just tend to business.’ I look around, I was hung up with

gangsters and everything else. So you get a gangster to play ball with

a gangster, you’re straight. I could relax and blow the horn like I

want. I got signed up with a cat, assured me he’s a

millionaire. He could give me a hundred thousand dollars on my

contract and it wouldn’t have done as good as telling one of those bad

sonofabitches, ‘Well, Joe Glaser is my manager.’ ‘Jesus Christ!’ See what I

mean? Where both of you all would be extorted all the time, every time you look

around, extortion, you and and your millionaire boss. Money ain’t all of

it. And then eventually you get a million dollars anyhow; peace of

mind. You know what I mean? If a sonofabitch ain’t always sticking you up for

this amount of money, that amount of money. Ain’t nobody bother you,

you still have what you want in the long run. And when you sum it up, it’s better."

In that same conversation, Armstrong made it clear that Glaser

had him set up if he ever needed to retire: "I don’t even know what

my income tax is no times and that alone, is heaven. You know all

them cats got their own bands, they got to figure it out. And Earl

and Big Sid, ‘Oh, I’ll pay it next week, well, maybe next week.’ And when you

look around, I don’t owe nobody nothing, nobody. Now you can’t beat

that. Peace of mind is the greatest thing in the

world. Cats come up to me, ‘Well, what the hell, what you do with your money?’ I say, ‘What you mean whatcha do with your money?’ I said, ‘Well,

Goddamn, anytime a sonofabitch could put a horn down tomorrow and get $200 a

week the rest of his life, he’s got to be doing something with

it. He’s got to have at least a hundred-thousand-dollar trust fund,

at least. And show me one colored man living that can bolster

that. Not your biggest. Isn’t that all right, Pops? If I

decide tomorrow I ain’t going to play no more trumpet, I’ll get $200 a week for

the rest of my life. If I live to be a thousand years old. Now

what’s more than that? And I ain’t thinking about putting the horn

down. So ain’t that enough consolation for anybody in the

world?"

Louis also made it clear that his wife Lucille wasn't the biggest

fan of Glaser’s methods, but he didn't care: "I don’t do nothing

behind Joe Glaser’s back. Nothing. I don’t sign nothing. You

know, we went through that experience and like Lucille said one time, ‘You

gotta let the white man do everything!?’ I said, ‘No, it ain’t

that! It ain’t one of them old fogey, phony things like

that. Here’s a man I know is in my corner and he’s just like a

father to me and we come up together. We’ve both had our ups and

downs. See? He’s been broke three times. He’s been a

millionaire three times. So you know he knows life and he knows his

friends, you understand? So it ain’t like that, see?’ ... But to Lucille,

I say, ‘Damn all that business, busting your brain. It ain’t gonna

happen no more.’ Anytime she want money, she go up to Joe Glaser and

he don’t ask her what she should take, or whatever; ‘What you want?' That’s

what he asks her, you know? If we don’t work for six months, every week she

could go in, just like I get my salary, and get whatever she wants. How in

the hell you going to beat that?"

Eight years later, speaking to his friend Babe Wallace in

Israel, Louis made it clear that such criticism still didn't bother him: "We ain't looked

back since we signed up with Joe, whether we work or not. There you go.

'Oh, that nigger making all that money for a white man.' So I just

keep saying, 'You ever see Louis Armstrong look like anybody who needs

something?' They say, 'No.' Well, what the hell? Figure that

out. You know? There's always some old spade who's going to say

some shit."

On and on I can go with stories of Louis in private praising

Glaser's way of handling Armstrong's business affairs. On a 1961 tape, Louis

barked at Lucille during a fight, "The horn comes first--then you and Joe

Glaser."

Having said that, it was definitely not all rosy. For all the

"Mr. Glaser" respect, Louis was not afraid to tear into Glaser when

he felt like he was being wronged. In a 1961 letter, he roared, "I think that I am

entitled a little bit somewhat as sort of being treated like a man instead [of]

just a Goddam Child all the time." Dan Morgenstern remembered

overhearing Louis on the phone with Glaser in the early 1960s, “giving as good

as he apparently was getting in the foulmouth department. No 'Mister Glaser' in

evidence there, but it ended calmly. Armstrong was never afraid of Glaser's

tough-guy demeanor." And Joe Muranyi remembered a blow-up on the road in

the late in 1960s where Muranyi heard Armstrong scream, "Joe Glaser thinks

we're a bunch of niggers!" to himself in his dressing room. It wasn’t

all “I love you” but longtime doctor Alexander Schiff described them as

“brothers” and that seems a little more accurate: they were almost the same

age, they started together as young men, and could yell and scream but at the

end of the day, they

did love each other.

Okay,

let’s now head to the problematic area: the years between Glaser’s death on

June 6, 1969 and Armstrong’s death on July 6, 1971. Glaser’s death had been

reported on for years. I am not a fan of James

Lincoln Colllier’s 1983 book, Louis

Armstrong: An American Genius, but Collier did interview Lucille Armstrong

at length, as well as Glaser associates such as David Gold and Doc Schiff. As

evidenced above, Lucille wasn’t the biggest fan of Glaser but she was the first

one to tell the story about Louis finding out Glaser was in a coma. Both men

were at Beth Israel Hospital but Lucille didn’t want to tell Louis about

Glaser’s condition (he had had a stroke). Then Dizzy Gillespie showed up, visited

Louis and said he was there to give blood to Glaser, telling Louis, “Joe

Glaser’s sick as a dog right around the corner in the hospital here.”

“Well,

the worst thing they could have told Louie was that,” Lucille told Collier.

“And when the doctor came Louie chewed the doctor out. By the time I got to the

hospital he had enough left in him to chew me out.” Louis was so shaken by his

visit to Glaser, he told Lucille, “I went down to see him and he didn’t know

me.”

That

seemed to be the story for about 35 years, until George Wein wrote his

autobiography in 2003. In it, Wein mentioned going to Armstrong’s home in

Corona in 1970 to film an interview with him for a documentary Wein was making

on his tribute to Louis at the Newport Jazz Festival. In his book, Wein

recapped the above story about Louis visiting Glaser in the hospital, but then added some new information:

"As

[Wein’s wife] Joyce and I spoke to Louis a year later, though, he told a

different story. 'When we started,' he said, recalling Chicago in the 1920s,

'we both had nothing. We were friends--we hung out together, ate together, we

went to restaurants together. But the minute we started to make money, Joe

Glaser was no longer my friend. In all those years, he never invited me to his

house. I was just a passport for him.' Louis was also offended by the fact that

Joe Glaser's will bequeathed Associated Booking, Glaser's company, to my friend

Oscar Cohen and several other people in the company. To Louis, he had only left

the rights to his own publishing. 'I built Associated Booking,' Louis said

angrily. 'There wouldn't have been an agency if it wasn't for me. And he didn't

even leave me a percentage of it.' Louis also described his bedside visit with

Glaser in the hospital. Joe Glaser was indeed in a coma, unable to communicate.

Louis, quite ill himself, seated in a hospital-issue wheelchair, leaned in to

whisper a message. It turned out to be the last words between them. What Louis

said was this: 'I'll bury you, you motherfucker.' Joyce, Sid Stiber, and myself

were present when Louis spoke these words. I don't doubt that his feelings of

resentment, which had many years to accrue, were sincere. In a sense, Louis may

have felt unburdened when Joe died; he was no longer under Glaser's managerial

yoke. With precious little time left in his own life, Louis may have simply

decided to air long-suppressed emotions."

Strong

stuff! I remember reading that in 2003 and thinking, “Wow! That changes

things!” But in the ensuing years, I began doing more and more research,

collecting every single time Armstrong mentioned Glaser in public and in

private after Glaser’s death. Suffice to say, I couldn’t find anything

resembling what he supposedly told Wein. Then I read the rest of Wein’s book

and it was clear that he hated Joe Glaser—and probably rightly so. Could you

imagine doing business with someone like Glaser? I have at least one letter

where Glaser angrily wrote to George Avakian about Wein recording Louis at

Newport in 1956. In 1957, Armstrong famously blew up backstage at Newport after

Wein tried getting him to change his All Stars set. In his book, Wein blames it

on Glaser and said Louis was ready to kill him. Again, not true. Audio survives

of the concert and Armstrong cheerfully dedicates “Lazy River” to Glaser

onstage. Dan Morgenstern was there (he’ll be telling his side of the story at

Satchmo Summerfest this year!) and told me that in no way was Armstrong

directly upset at Glaser.

So

after digging deeper and realizing Wein might have had a little personal

vendetta, I decided to leave his story out of my Armstrong biography, saving it

for a footnote but even mentioning there that it was the only such story about

Armstrong feeling betrayed by Glaser.

Flash

forward to the summer of 2011. My book is finally published and I go to dinner

with Terry Teachout to celebrate at Birdland. Terry praises my book, but says

there’s one thing he had a problem with: I left out Wein’s story and went easy

on Glaser. I told him I didn’t quite buy Wein's story. And that’s when Terry said, “It’s on

film! George filmed it!”

I

felt my insides cramp up a bit. Yes, Wein filmed Louis at home for his Newport

documentary….but the Glaser venting was captured on film? How did I not know

this? I immediately began regretting my decision to go lightly on this matter.

But

not for long. A few months later, the late Phoebe Jacobs contacted me to have

me interview involved with the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation. She set

up an interview with George Wein, the first time I had ever met him. We talked

all about Louis but as often as he could, he’d slam Glaser, saying how Louis

“hated” him. Finally, I had to ask: “Does he still have the film of everything

he shot for Newport?” Yes, he does. “Did he film Louis talking about Joe

Glaser?”

“No,”

Wein said, looking down, “I didn’t film that, it was after the interview.” (Wein has released the complete audio of his two 1970 interviews on the Wolfgang's Vault website; one mention of Glaser and it's a friendly one.) And

that’s when he got a little annoyed and said this to me:

"Of

course, a lot of people, with the legend of Louie and Joe, you know, they were

upset with that although they understand that, you know--you have to understand

that sociologically, there was something necessary but also something wrong

with the kind of relationship that Louie [and Glaser had]. That wrong had to be

corrected. Since then, it has been corrected with other people. And so when I

told that story, it was a sociological reason for telling it. It had nothing to

do with Joe Glaser or Louie. It was a white man with a black man and the white

man owned the black man and the black man who was supposedly 'yessuh massa,'

hated him. And that was the reason I told that story. If I hadn't my wife with

me and we hadn't known--and Sid Stiber was with me—to hear those things

directly, I would never have said it because people wouldn't [believe it]—but

now everyone's gone so it doesn't make any difference. But that was the reason

that I told it because it was wrong. That doesn't mean that Joe Glaser didn't

help Louis Armstrong become the big star he became; he did. And that doesn't

mean Louis Armstrong didn't make Joe Glaser the major agent he was. I mean,

they both benefitted. But the relationship that was built just wasn't—and for

people to think that those things are those kind of love affairs, they're NOT

those kinds of love affairs. And that's the reason that I told that

story."

Now

you can make of that what you will. “It had nothing to do with Joe Glaser or

Louie.” Wein hated Glaser and was disgusted by their relationship. Did he make

up that entire story just to show his disdain for their relationship and how it was "wrong" sociologically? (Another note: Wein told me he enjoyed Pops and Terry reported that Wein saw Satchmo at the Waldorf and raved.)

The

only thing I could do was research, research, research. So here is a handy

timeline of all Armstrong references to Glaser from 1969-1971 that have

survived besides Wein’s.

c. June 1969 - Karnofsky

manuscript dedication

While in Beth Israel in March 1969, Armstrong began working

on a manuscript about his relationship with the Jewish Karnofsky family in New

Orleans. While there, Glaser had a stroke and was admitted. Armstrong ended up

going home in April but Glaser died in June. Armstrong continued working on the

Karnofsky manuscript into 1970 and some point after Glaser died, penned this

dedication on page 3:

I dedicate this book

To my manager and pal

Mr. Joe Glaser

The best Friend

That I’ve ever had

Ma the Lord Bless Him

Watch over him always

His boy + disciple who

loved him dearly.

Louis

Satchmo

Armstrong

June 28, 1969 - Private letter to Leonard Feather

Louis to Feather, 22 days after Glaser’s passing:

“We are just about cooling down over the passing of our dear

pal Mr. Glaser. Lucille and myself went to the church service where he was laid

out. A real nice funeral. Everybody were there …all of his admirers and

acts….Dr. Alexander Schiff managed all of the funeral arrangements. He was with

Mr. Glaser at the hospital the whole time he was sick , and when he passed. So

many people were there, I could only wave at them.”

Even with Glaser gone, Armstrong was intent on performing

again: “I am just waiting—resting—blowing just enough to keep the chops in

shape, in other words, to keep my embrasure

up ‘ya dig.’ That’s a big word that I very seldom use. Anyway it all sums

up that I’m about to feel like my old self again. I never squawk about

anything. I feel like this—as long as a person is still breathing, he’s got a

chance, right?”

June 29, 1969 –

Glaser’s will delivered to Armstrong

We have Louis’s copy of Glaser’s will at the Armstrong

House. It was postmarked on June 29, 1969, so he knew exactly what he was

getting. Associated Booking also signed him to a brand new contract around the

same time. Much more on this later.

July 29, 1969 –

Private letter to Little Brother Montgomery

Louis, now knowing the contents of the will and what he was

getting, writes a private letter to musician Little Brother Montgomery .

“Man, I was a sick ass. Yes, my manager + my God Joe Glaser

was sick at the same time. And it was a toss up between us—who would cut out

first. Man it broke my heart that it was him. I love that man which the world

already knows. I prayed, as sick as I was that he would make it. God Bless his

Soul. He was the greatest for me + all the spades that he handled.”

Armstrong closed by mentioning he was feeling fine and ready

to be “back on the mound again,” though he warned about “fewer one-niters HA

HA.” He would not perform in concert for 14 more months.

January 21-23, 1970 –

Letter to Oscar Cohen

Admittedly, this is a somewhat uncomfortable letter because

Cohen was now Associated Booking Corporation’s President and Louis’s praise in

this letter could be seen as a bit thick, a way to insure that ABC would still

book him. Armstrong now knows the entire contents of the will and sure doesn’t

show any animosity about Cohen being president, writing, “And now that you are

president which I think you so rightfully deserve (who else?).” It’s no surprise that the praise for

Glaser is pretty thorough here, too: “Mr. Glaser was the man who really Dug’d

me and realized that what I was really putting down as far those other Big name

ass holes were concerned. That’s why I will low his dirty drawers as long as I

live.” Still, it’s not inconsistent with the rest of Louis’s public and private

utterances about Glaser in the last two years of his life. Louis really digs

into the story of Glaser putting Louis’s name in lights at the Sunset Café in

1927 and concludes, “I could go on forever writing about the man you + I Love.

He was so great. I am + you realize that. So let’s you + I keep him happy.

Although he’s passed. It doesn’t mean a thing as far as we’re concerned.

Because you and I loved him so. The Lord above knows that we’re gonna do

everything that we know that will make Joe Glaser happy.”

Early 1970 – Letter

to Max Jones

Louis wrote a lot of letters to Max Jones in 1970, giving

him information for the eventual books, Salute

to Satchmo in 1970, and Louis in 1971.

Jones never published dates but in this letter, Armstrong mentions his new

record of “We Have All the Time in the World” so it’s at least early 1970:

“You must understand I did not get real happy until I got

with my man—my dearest friend—Joe Glaser (Yea man). Nobody will ever touch that

man in my books. I can go all night and all day talking about that man.”

Armstrong then told his favorite story about the advice he got from “Slippers”

when he was a young man ready to leave New Orleans: “He came right over to me

and said, ‘When you go up north, Dipper, be sure and get yourself a white man

that will put his hand on your shoulder and say ‘This is my nigger.’ Those were

his exact words. He was a crude sonofabitch but loved me and my music. And he

was right then because the white man was Joe Glaser. Dig, Gate?”

These quotes seem to be from a later letter in 1970:

On the All Stars: “It was Joe’s idea. After all he’s the man

who has guided me through my career. Coming from the man I love, who I knew was

in my corner, it was no problem for me to change. I didn’t care who liked it or

disliked it. Joe Glaser gave the orders and nobody else mattered to me. You

see, I knew he was concerned about my life in music. He proved it in many

ways….But always remember one thing. Anything that I have done musically since

I signed up with Joe Glaser at the Sunset, it was his suggestions. Or orders, whatever you may call it. With me,

Joe’s words were law. I only signed but one contract with him, and that was

forty years ago. And that still stands. Of course, I am still with the Office,

and everybody that is still in his Office feels the same about us. So now you

know just what was in the background of all my musical activities.”

February 11, 1970 –

David Frost Show

Louis tells the story of the advice he got from Slippers in

New Orleans to stunned silence. After the "always have a white man behind you" part, Armstrong added, "Now that’s the way he put it

to me. Now you can figure that out yourself. That’s what we’re talking about.

[Armstrong smiles broadly] And Joe Glaser came right in the scene. We was just

like that. [Holds his fingers close together] Because he knew I wanted to blow

my horn and he saw to that. I didn’t worry about battles and this and that–Joe

knew that if I didn’t find him, I was going on back [to New Orleans] because I

knew they loved the way I blew my horn in that honky-tonk.”

May 25, 1970 – The

Mike Douglas Show

Insult comic Jack E. Leonard was on the panel with Louis. It

turns out Leonard used to be a Charleston dancer at the Sunset Café in the

1920s. Here’s part of the conversation.

LA (to Mike Douglas): Hey, you know he used to work with Joe

Glaser?

JEL: Everybody worked for Joe Glaser!

LA: That’s right.

JEL: Joe Glaser, may God rest his soul, he was one of my

dearest friends, he used to give me $2 a night for Charleston contests, before

he died, he said to me, “Jack, I’ll give you $3 now.”

LA: He was a good man.

JEL: He loved you, Louie. How long were you with him?

LA: About 40 years.

JEL: 40 years.

LA: Beautiful years, man.

May 29, 1970 – The

Mike Douglas Show

Douglas asks Louis to name his “Five Most Admired People.”

After Lucille and Dr. Gary Zucker, he names Joe Glaser and once again tells the

Slippers story:

LA: That's my manager for over 40 years.

MD: He took care of you, didn't he?

LA: And one of the best friends I've ever had. When that bad

colored boy down in the honky tonks, that like to hear me play the blues, and

he knew I was going up north, you know, to play with King Oliver, the first

thing he said was, "You get you a white man to put his hand on your

shoulder and say, 'That's my nigger.'" He meant from his heart. That's the

only way he could tell me. Them people didn't have nothing or too much

education, but whatever they said, it was [from the] heart. He wouldn't tell

that to nobody else. He'd rather shoot you first, you know? But for me, Joe

Glaser was that man. Joe Glaser, 'Aw you nuts.' I went, 'No, you my man!' And

that what happened.

MD: And he took care of you?

LA: Took care of me?

I ain't asked nobody for nothing yet, that's all. (shows off suit) This

vine ain't looking too bad, is it? (laughter) That shows, I mean, the vonce was

there! So that's my man.

(Above portion in bold because I will return to it.)

Later, Mike asks Sammy Davis about Glaser. Sammy gives long

tribute after complaining earlier about not being sent overseas to entertain

the troops during Vietnam. Louis interrupts and says, “Joe would have sent him

over there! Yes he would have.” Then Sammy says:

SD: You never read about a Joe Glaser act being in tax

trouble for $140,000 because he'd give it to you himself.

LA: Or pay it.

SD: Pay it! He'd pay it.

LA: I never did owe nobody anything. No trouble. All my

income tax. He always stayed in the background but he'd always come to

you.

August-September 1970

– Letter to Max Jones

In July 1970, Louis told David Frost, “Yeah, I’m gonna tell

it all to Max Jones for the first time—the way it really was.” He made good on that by sending Jones a letter in

August that was all about the joys of marijuana. Combined with the Karnofsky

manuscript he was working on concurrently, Louis was all about setting the

record straight in the summer of 1970. But between both documents, Louis only

had praise for Glaser. In August, Jones sent Armstrong a list of questions to

answer and didn’t ask about Glaser, so Glaser is only mentioned twice but both

times, in positive light:

“It was Joe Glaser at the Sunset who first put my name up.

He had a big sign saying ‘Louis Armstrong World’s Greatest Trumpeter.’ He heard

someone say, ‘Who put that up?’ ‘I did,’ he said, ‘and I defy anyone to move

it.’”

“After I came back from Europe the second time, I stayed

around Chicago then Joe Glaser who I’d worked for at the Sunset became my

manager. Our first contract was for ten years, after that we didn’t bother,

don’t know whether I was right or wrong but I was happy. He stuck by me.”

January 11, 1971 –

Joe Delaney Radio Interview

This interview took place in Vegas when Louis was towards

the end of a two-week gig with the All Stars shortly before the Waldorf engagement. Louis is in good humor

throughout. Delaney mentions that Louis would give money away to relatives but

he had “five dollar relatives and ten dollar relatives.” Louis laughs and takes

it from there:

LA: I’m like Joe Glaser, you know, I had five-dollar

pockets, you know, a one-dollar pocket. You go up to Joe Glaser’s and say,

‘Give me a hundred dollars,’ he reach somewhere, he’d find it!

JD: A hundred dollar pocket!

LA: Thousands! I learned that from Mr. Joe Glaser.

JD: You know, Louie, I think that in the annals of show

business, one of the great relationships has been that of Joe and yourself. Joe

passed away last year but you two were together for about 40 years.

LA: Oh, beautiful memories of that man. He was too much.

JD: The exchange of correspondence between you two would

make a great book.

LA: Oh yeah, I’m writing a letter, a lot of memories

[between] Mr. Glaser and myself. Them days in Chicago at the Sunset. And it’s

so beautiful.

[This might refer to the aforementioned letter to Oscar

Cohen which goes on for 32 pages mostly about Glaser and the Sunset.]

February 22, 1971 –

Dick Cavett Show (promoting the Waldorf engagement)

After playing two numbers and being interviewed by Cavett,

Louis stayed on the panel when Kaye Ballard came out. The camera cut to Louis absolutely beaming with pride while she spoke about Glaser.

KB: And you

know, it’s so funny, because my darling Louie Armstrong, we had the same agent

who meant a lot to Louie and a lot to myself, Joe Glaser. He was one of the

last of the originals. [camera cuts to Louis, looking sick, but beaming] I used to call him ‘Mighty.’ And I’d

say, ‘Mighty, I need to pay the rent!’ And it would be there in the afternoon

without a million papers to sign or anything like that. And those people aren’t

around anymore.

DC: Are you sure he was an agent?

KB: [Laughs] Yes. And he was the best! Mighty Joe Glaser.

LA: A great man.

DC: Yeah, I used to hear that a lot about him. His clients

had great affection for him.

KB: You know, Dick, it’s thrilling to be hear with Louie

because…

LA: Everybody loved Joe Glaser. Everybody.

DC: How old was he when he died?

LA: Well, he’s three years older than I am and I’m 70 years

old and he was 73 when he died. And to me, he was Jesus. That’s how much I

thought of him.

That concludes all of the times I can find that Louis

mentioned Glaser in those last two years. When Terry brought John Douglas

Thompson to the Armstrong Archives, I showed them that last Cavett clip. Terry

immediately explained it away as Armstrong being on television and needing to

say that to keep Associated Booking happy. But the above list includes some private

letters that Armstrong sure didn’t expect to be published. And on top of that,

he continued to pay tribute to Glaser in other private ways:

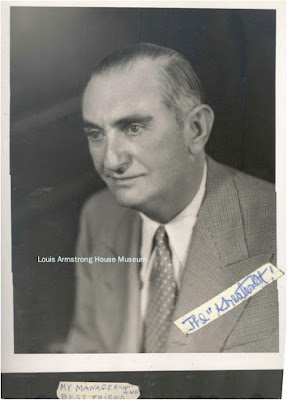

Scrapbook – c. 1970

Personal scrapbook made by Louis containing documents dated

from July 1969 through January 1970 but also including some photos definitely

from 1970. Somewhere in there Louis included a photo of Joe Glaser and wrote on

it, “The Greatest!” and “My manager and best friend,” using the white athletic

tape he used consistently on his reel-to-reel tapes between 1969 and 1971:

The final collages.

When Louis got home from intensive care in April 1969, he

started working on his tape collection, renumbering them from number “1.” By

the time of the Waldorf gig, he got to “170,” each one done with white athletic

tape and handwritten reel numbers. Louis had a very slow start; in one of the

early 1970 interviews, he mentioned that he had only done one small shelf but

then I think he spent almost all of his free time in 1970 cataloging the tapes

and making new collages. So I can’t date these, but they’re all 1970-1971. In

this first example, “Reel 59,” he used a memorial statement he had printed up

after Glaser’s passing:

This continued in “Reel 60,” where Armstrong included

another tribute to Glaser, edited from the Karnofsky manuscript dedication:

The front of “Reel 60” includes a photo of Louis and Glaser

together at Carnegie Hall in 1965:

Armstrong’s still at it on “Reel 86,” with another new

collage in tribute to his old boss (“Reel 87” included a short clip of TV news

coverage of Glaser’s funeral, sent to Armstrong by his friend Tony Janak):

By Reels 140 and 141, we are at the end of 1970, possibly

early 1971 (“Reel 133” included Louis’s October 1970 appearances on The Flip Wilson Show and The Johnny Cash Show). Yet here’s young Joe

Glaser and his mother Bertha on “Reel 140”:

And finally, a newspaper tribute to Glaser, with Armstrong

superimposing Glaser’s signature on the collage that makes up the back of “Reel

141”:

Between the private letters, the TV appearances, the radio

appearances, the scrapbook tribute and the tape box collages, that’s a lot of love for Glaser in the two years

after he died. Why would he make collages dedicated to someone he hated? The

only dissenting voice is Wein’s and even Wein admitted to me, he basically felt

the need to tell such a story because he found so much wrong about Armstrong

and Glaser’s relationship.

But from that one paragraph, we now have Satchmo at the Waldorf. Again, SPOILER SPOILER

SPOILER but these are some excerpts of the climactic moment of the play, when the character of “Armstrong” in 1971 talks about Glaser’s death and how his will left him “nothing” (note: this is my

transcription and might not reflect the actual script 100% faithfully):

“Next thing I know, he’s gone and that’s when I found out

what a stupid sonofabitch I have been my whole life. It really stung me when Mr. Glaser didn’t leave me nothing in his

will. Nothing but a little cash…. But the thing is, I figured he was going to

leave me a piece of the business, too, like he should have done. Like I

deserved. I mean, he called it Associated Booking Incorporated, but he could

have called it Armstrong and Glaser Incorporated cause there wouldn’t be no

Associated Booking if it wasn’t for me. … I figured he gonna make damn sure ol’

Satchmo taken care of down the line. It’s kind of my birthright, you know?

Maybe I’m just another dumbass fool, but that’s the way I figured it. And there

wasn’t nothing for me? Not one goddamn share? It felt like he kicked me right

in the nuts, used me up and threw me out....Can’t believe I’m talking like this now.

Ain’t never talk like this about Mr. Glaser. Never even let myself think it.

Always told folks he was the greatest. But now I look back and I see it plain

as daylight. …Man worked my ass like a blue-black fieldhand. Built his whole

damn business on my back and then he don’t even leave me a piece of it when he

die? Motherfucker screwed me! Screwed me to the wall! All he did was leave me a

tip! And that hurt, hurt me bad. That shit ain’t right. I thought Joe Glaser

was my friend and he treat me like a nigger!”

At this point, “Armstrong” almost dies onstage, coughing and

wheezing and barely making his way to his oxygen tank. It’s great drama and

John Douglas Thompson really sells it. Both times I saw it, the theater was

chilled to the bone, silent. And in that silence, the theatergoers draw their

conclusions: Louis Armstrong was screwed by his manager, hated himself over it

and had to continue working just to make a few bucks.

That’s how the New York Post reporter

explained it to me. A friend saw it in Los Angeles and wrote to me, “The play

gives the impression that Louis died broke.”

Now—MORE SPOILERS—Terry does have one final twist. Glaser was

forced into joint ownership of Associated Booking in 1962 by famed mob lawyer

Sid Korshak. This is true. Terry’s “Glaser” character explains that because of

Korshak, “Glaser” couldn’t leave “Armstrong” anything in his will and that

“Glaser” knew this and couldn’t bring himself to ever tell “Armstrong.”

“Glaser’s” confession makes him a sympathetic character but it does nothing to

erase the sad spectacle of broke, dying “Armstrong” onstage.

So let’s get to the main event now, the finances. I’ve

already explained that Glaser paid just about everything Louis and Lucille ever

asked for. This is an instructive passage from Glaser to Lucille on May 28,

1968, when Lucille wanted to start remodeling her and Louis’s home in Corona,

Queens:

“I already instructed Dave Gold to send a check at once for

$2,500 to Morris Interiors as per your request and since I am sure Louis will

meet with Lionel Crane tomorrow or the next day as he is coming in from London

to write a special feature story on Louis, tell Louis to put his mind at ease

as this $2,500 that Louis is receiving is going to be applied to Louis account

and Louis will not be obligated to pay a penny of it or take the money out of

the bank. There is no need saying it will always be a pleasure to do everything

I can where you and Louis are concerned and I am very happy he is feeling ok

and I am sure he is getting plenty of rest.”

Not the tough Glaser you might expect and sure enough, Lucille began remodeling a few weeks later. Glaser died in

June of 1969 so let’s look at his will. There’s lots of interesting things,

naturally. Sidney Korshak—“my dear friend”—got 5% of ABC. The will does mention

a “certain Voting Trust Agreement bearing date of August 23, 1962, wherein all

of the voting rights, dominion and control of said shares of stock have been

assigned to SIDNEY R. KORSHAK and myself as joint trustees for the purpose

of executing and carrying out said Voting Trust Agreement.” Sounds important

but though I’m no lawyer, it doesn’t seem like Glaser sold his life away.

In fact, he split up ABC among many employees and even had

gifts for others. There’s a whole list of people he bought bonds for; Dr.

Schiff got his diamond signet ring, diamond belt buckle "and one of my

good watches”; Dr. Harold Cohen also got a diamond and platinum ring.

Then there’s Louis, with a section of his own:

"I give and bequeath all my right, title interest,

legal and equitable, in and to all shares of stock of INTERNATIONAL MUSIC,

INC., which I may own or have at the time of my passing to my friend, LOUIS

ARMSTRONG, and in the event of his death to his wife, Lucille."

This might not sound like much but believe me, it is more

than “a tip.” International Music was Joe Glaser’s publishing firm and it

controlled all the royalties of Armstrong’s compositions as well as those of

Lillian Hardin and various other ABC acts. It was the gift that kept giving as

long as Armstrong music continued to sell (it still continues to sell). Long

after Louis and Lucille died, David Gold told a trustee of the Louis Armstrong

Educational Foundation to check International Music because “that’s where the

money is.” Giving Armstrong all of

International Music insured a steady income that benefitted Louis and Lucille

for years to come. Remember, Lucille could have “left” Associated Booking after

Louis died; she didn’t. They continued to oversee her bills and payments until

her death in 1983. Except for lectures and public appearances, she never had to

work a day after Louis died.

Also—and perhaps even more importantly—as Lucille herself

mentioned in the Collier book, Glaser did

have an account for Louis at ABC and though it is not referenced in his

will, Oscar Cohen and David Gold made sure to turn it over to the Armstrong’s

immediately. Collier talked to Gold and to Lucille and reported, “Glaser had also set aside money in savings accounts and trust funds, all of which was turned over to the Armstrongs after his death....Furthermore, on Glaser's death the firm turned over to Louis and

Lucille everything it had been holding for them. Dave Gold, vice-president and

treasurer of the Glaser office, said, 'Because of the unique nature between

Glaser and the Armstrongs, at that point we felt that rather than create any

question of propriety, we felt it best that they handle their own funds.' The

firm arranged for independent accountants to take charge, with Lucille, more

than Louis, involved in major financial decisions."

This must have happened immediately

because Glaser died on June 6 and on June 12, Cohen and Gold had Louis sign a

brand new contract with ABC, something he hadn’t done since 1935. I suppose the new heads of the company

thought would be a good faith gesture to let Armstrong know that they wanted to

continue representing him.

Louis bragged in those earlier quotes I

shared about Glaser having a “trust fund” for him. We might never know what was

in it but as the Collier quote illustrates, it was substantial. Armstrong's close friend Ernie Anderson later wrote in depth about Louis and Glaser (he was the first to publicly run with the Korshak connection) and he reported, "But, in some mysterious way, Joe's will made Louis a rich man....[Armstrong] told Bobby Hackett, who was very close to him, that it amounted to 'a bit more than two million dollars.'"

With the "mysterious" money from the ABC account, Lucille continued remodeling the Corona

home. At the Armstrong Archives, we have dozens of invoices from 1968 through

1970; I haven’t counted, but there must be $40-50,000 worth of work performed

in those years. In December 1969, Lucille led the charge to start the “Louis

Armstrong Educational Foundation,” using their own money to do it (Phoebe

Jacobs said it cost $40,000). In 1970, the Armstrong’s purchased the home next

door, knocked it down and Lucille began installing a lavish, Japanese-inspired

garden, which was completed in 1971, just before Louis’s death. Also in 1971,

the Armstrong’s decided to have their home covered in brick, along with

building a new brick wall that extended to the new garden property, as well as neighbor

Adele Heraldo’s house.

So the Armstrong’s were not sitting

around, broke, lamenting how Joe Glaser robbed and cheated them; they were

spending a lot of money, more than they had in quite some time. It was almost

as if Lucille was freed from the Glaser relationship, got the lump sum of money

and began spending it on all of these projects.

But Louis was sitting around—and happy to brag about it. Louis entered Beth

Israel the first time in September 1968, came home later that year, went back

in early 1969 and was released in the spring. After two stints in intensive

care, Armstrong’s doctors forbade him from performing. For over 50 years, Louis

played night after night but now he was home, unable to perform. Associated

Booking got him a few high-paying jobs—singing in a James Bond film, getting

$25,000 for a Midas commercial—but there was no more nightly income. In 1970,

he began appearing on numerous television talk shows, but again, not for much

money.

But it’s on these talk shows where

Armstrong began to brag about his good financial standing. I’ll repeat this

passage from The Mike Douglas Show in

May 1970:

MD: And [Glaser] took care of you?

LA: Took care of me? I ain't asked nobody for nothing yet,

that's all. (shows off suit) This vine ain't looking too bad, is it? (laughter)

That shows, I mean, the vonce was there! So that's my man.

Before Armstrong’s July 3, 1970

birthday celebration in Los Angeles, Armstrong was interviewed by Bill Stout of

CBS News. Stout made the mistake of asking, “How do you feel about not being

able to blow your horn?” Armstrong did not appreciate the phrase “not being

able” and fought back, saying, “Who said I’m not able to blow? I blow every day

at my house!” Stout replied, “Yeah, but you aren’t supposed to work.” Armstrong

didn’t wait a second, barking, “I don’t have to work! I’ve got enough money so

I don’t have to worry about it. I play when I want.”

Armstrong’s eventually did go back to

work but it wasn’t out of necessity; it’s what he lived for. He did

two successful weeks in Vegas in September 1970, saying afterwards, “Let me tell you something. I

lived two years just waiting for that opening night.” Armstrong was back and

was determined to stay there even if it killed him. Which it did.

To me, that is the story of Armstrong’s Waldorf gig: a practically dying

legend fights to perform for his fans one last time. That is the drama, not Armstrong complaining about Joe Glaser’s

will and his being broke.

But Armstrong did die in 1971 and now

it was time to see his financial state.

Multiple Armstrong biographies have published this magic number: $530,275.65

That is what Armstrong’s estate was valued at the time of his 1971 passing,

about $3 million in 2015 money. Writers have always been quick to say, “Ah ha!”

when confronted by this number because Armstrong’s $530,000 is so much lower

than the $3 million Glaser left behind.

Not so fast. The government also realized that that number seemed a little low so they audited the

Armstrong estate. In 1976, they turned in their findings: the actual value was

Louis’s estate was $1,116,833.65! How did it go up? The

1971 estate value conveniently left out $560,000 of royalties! Oops! One can’t

blame the Armstrong estate (which was overseen by David Gold) for trying to

lower the number because a lower number meant a lower tax they’d have to pay.

But $560,000 is a lot of money to leave out, especially when it consists of

royalties, Louis and Lucille’s

International Music shares. (And yes, Armstrong's $1.1 million is less than Glaser's $3 million but remember that Armstrong gave away money his entire life; Glaser had no kids, wasn't married, was tight with a dollar and represented a bunch of other popular clients from Duke Ellington to Billie Holiday to Barbra Streisand and beyond.)

Examining Louis’s estate yields some

interesting finds. The 100 shares of International Music stock were valued at

$12,000 ($70,000 in 2015) but like I’ve said, they continued to bring money in

every year. There were also $13,600 in bonds, and $9,500 in real estate, which

must have also been set up by Glaser. Most interestingly, there were $57,000 in

bonds in separate bonds purchased monthly beginning in February 1962, just a

few months before Korshak moved into ABC; could Glaser have been purchasing

those bonds on the side as a means of extra protection? And even at the time

of his death, Armstrong had an $18,867.82 credit at Associated Booking (the Waldorf gig netted him $15,000 in two weeks). Louis

bragged about staying out of business and investment decisions so that’s about

$106,000 ($620,000 in 2015) that can be traced to Glaser, plus the regular

International Music royalties and the presumably large lump sum turned over

after his passing.

However you slice it, Armstrong barely

worked in the last three years of his life and started a Foundation, remodeled

his home, bought the house next door, knocked it down, installed a garden,

bricked up his house, etc. and still left a value of $1.116.833.65 (about $6.5

million in 2015 money); he had more than a

“tip” from Joe Glaser to work from. Remember what Louis said in 1951: “Money ain’t all of

it. And then eventually you get a million dollars anyhow; peace of

mind.” Louis had peace of mind his whole life and his million dollars when he died. (And so did Lucille, who

died in 1983 without needing to work and left an estate of $991,055.43.)

I could keep going but after 9,000 words, I think I should stop! Still, there are two more things I keep getting asked about and I might as well address them quickly, too: "Did Miles Davis really hate Louis Armstrong?" and "Did Louis Armstrong really hate his white fans?" I think if Terry were asked either of those questions, he, too, would answer, "No!" but regular folks are coming away from the play with those thoughts in their mind, so something is triggering this way of thinking.

Ethan Iverson already did a great job writing about Satchmo at the Waldorf's problematic portrayal of Miles Davis. Terry's "Miles" praises Armstrong's trumpet playing but criticizes his "Uncle Tomming" on stage. He also makes it clear that he hates white people, whereas Louis loves them. But the bulk of Miles's quotes come from his suspect autobiography; as Iverson makes clear, Davis almost always spoke positively about Louis during Louis's lifetime. (Interestingly, Dizzy Gillespie blasted Armstrong much more harshly but Armstrong never returned the favor; Gillespie repented in his autobiography.) The second time I saw Satchmo at the Waldorf, I went with Dan Morgenstern and afterwards, he held court outside the theater (in the rain) to talk about going to see Louis at Basin Street in 1961. Not only was Miles in attendance, but he shushed members of his party when they were talking during the music and clearly enjoyed every second of Louis's performance. And perhaps my favorite Miles quote on Louis came when he was interviewed by Bill Boggs in the 1980s: "[Those who see Louis as an Uncle Tom] don't realize that Louis was doing that when he was around his friends. You know he was acting the same way. But when you do it in front of white folks, and try to make them enjoy what you feel--that's all he was doing--they call him 'Uncle Tom.'" Well put, Miles Davis.

And speaking of white folks, it can not be argued that by the time of the Waldorf gig, Armstrong was playing for almost exclusively white audiences. In Satchmo at the Waldorf, Armstrong talks about the hurt he felt in watching his black audience abandon him (true) but he blames himself in an episode of out-of-character self-pitying, more or less saying that Joe Glaser told him to clown around and "sing pretty" to lure the white audience. Glaser actually did say something like that in the Life cover story of Louis in 1966 but it wasn't true when he said it either. Armstrong was singing pretty ("I Can't Give You Anything But Love," "I'm Confessin'," "Body and Soul," etc.) and making faces (his 1920s live performance reviews almost focused exclusively on his showmanship) long before Glaser took over his career in 1935 (and for almost exclusively black audiences, too). And as Armstrong always was quick to point out, no one could tell him what to do onstage.

In the play, Armstrong disparages his audience as a "carton of eggs" and towards the end, thinking about playing in front of them instead of black fans, wonders, "What the fuck happened?" Armstrong was too stubborn to ever beat himself up that much. He was 100% real at all times and if you didn't appreciate it, it was your loss. He bristled at being a clown ("A clown is when you can't hit a note!" he said in 1959) and once shouted on one of his tapes, "When the fuck have I ever Uncle Tommed!?" so he sure wasn't doing that stuff with a strategy in mind; it was him.

Recently, I acquired video of Armstrong being interviewed in England in 1968. When asked, "Do you think your warm, emotional kind of entertaining can make better friends between black and white people?" Armstrong smiled and answered with a joke. "I think so," he said. "I mean, I'm black and I have a lot of white fans, so you've got it in technicolor there!"

Armstrong smiled, looked right into the camera and winked. But all of a sudden, the joy disappeared as he thought more about the question. "See what I mean? White people are responsible for all my success. And I don't care how much they march or whatever--I mean, after all, white people, they stood behind Satch to put him right where he is. So you know I got to love them. Ain't nobody gonna tell me nothing. I send in my donations for the cause, whatever they're doing, you know, for the Negro, to the extent. But the Negro didn't put me where I am today, the white people did. Watch that."

Growing angrier, Armstrong remembered a story about playing in the same town as Louis Jordan in the 1950s, something Marty Napoleon witnessed and something Louis told Jack Bradley about in the 1960s (both men told it to me for my book). Louis doesn't mention Jordan by name here but that's who he's referring too: "I played in Dallas, Texas at the Coliseum and they paid a lot of money for our attraction. But at the next block, they had one of them zoot suit saxophone players playing all that [imitates boogie-woogie eight-to-the-bar sound], you know what I mean, the trend--but still in all [Louis makes a first, shakes it powerfully, closes his eyes and nods seriously]--like Mozart. Them people came to see Satch and they was all white. I could count the colored there. That's the night--I remembered that. See what I mean? So now, on the rebound, the credit goes to the WHIIIITTTTE PEOPLE! Period!"

Armstrong is scowling when he shouts, "Period!" and I've never heard him phrase anything like he does, "white people," drawing out the word "white" like a bent note on his trumpet. Again, this is the reality. There's plenty of drama in Armstrong losing his black audience and how he resented them for that, but I don't feel he scorned his white fans one bit. As he put it himself there, they're the ones who treated his music like Mozart and he didn't forget that. (Though I'm sure he'd be proud to see his standing with African-Americans change back towards the positive after the influence of Wynton Marsalis in the 1980s.)

Geez, I did not expect to write 10,000 words

on this subject but I thought it was important to publish the facts. I should also

mention that nobody asked me to write this; there was no pressure from the

Armstrong House, the Armstrong Foundation or anyone else. And I am not a full-blown Glaser apologist; my

book includes plenty of stories of Glaser being too crude and messing with

Armstrong’s recorded legacy (why, oh why, did he pull Armstrong off Columbia in the 1950s before he could record with the Ellington big band or Gil Evans!?).

But I want to close by mentioning someone who is really far from a Glaser fan: Louis’s longtime friend, Jack Bradley. Jack is still

alive, 81-years-old now, and still as feisty as ever. He was as close as anyone

could be to Louis from 1959-1971, referred to by Louis as his "white son." As a photographer and associate of Armstrong's, he dealt with Glaser often and didn’t like him, blaming him for not being sympathetic to Louis's needs and for having a somewhat racist side.

Once, in the late 60s, Jack made the mistake of criticizing Glaser while having dinner at the Armstrong’s home and Louis, without even looking

up, cursed Jack out so harshly, Jack got up and left, crying. Armstrong could

explode like that but the next time he saw Jack, everything was back to normal.

It still shakes Jack up to this day.

But Jack was Louis constantly during

those years and especially during that 1969-1971 period when Louis spent so

much time at home. When I saw Satchmo at

the Waldorf, I called Jack and told him about everything, especially Louis

venting about Glaser after Glaser's death. You could hear the laughter from Cape Cod. “HA HA HA HA HA!”

he shouted into the phone before moaning, “Oh no! Jesus Christ, of all things!”

Just to make sure I wasn’t nuts, I asked Jack one more time if he ever

remembered Louis feeling resentment towards Glaser. “No!” came the reply. “Not

once! Louis wouldn’t let anyone talk

about Glaser like that, let alone himself. I didn’t even like Joe Glaser but that’s ridiculous. Oh, Louis is probably

spinning in his grave!”

Let me reiterate a few things (if

you’re still awake): Terry Teachout did the Armstrong community a service by

writing Pops and Satchmo at the Waldorf is a great evening at the theater;

seriously, John Douglas Thompson will knock your socks off. But each night, a

sold-out theater of attendees leaves pitying poor, taken-advantage-of, broke

Louis Armstrong and I just wanted to do something to counter it because in my opinion, this work of fiction might be based freely on fact, but it's also based freely on fiction. Sometimes, the truth is not only

stranger than fiction, it makes for better drama.

Comments

As usual, thanks for this, Ricky. What you do here is give the necessary antidote for those who are inspired to look more closely at Pops, to listen to his music, and learn his story. For those people this is invaluable. For the rest, who will never look further and who will carry a mistaken notion about Louis around in their heads – well, alas – let the zoomers drool.

And remember, John S. Wilson could never hide his contempt for Armstrong and the All Stars but he went to the Waldorf and gave the opening a fine review. So if something ever did turn up, if it was from the early part of the stay, I think we'd be surprised. But as the two weeks wore on, Pops wore out and the stories I've heard paint a bleak picture of his trumpet playing by the end. Sad….but oh, how I'd love to hear something from that engagement!

Ricky

By the time I started writing my book, only five members of Armstrong's band were alive (two were black), but they all reiterated how close Armstrong and Glaser were. But perhaps you'll find this interesting. In my blog, I quoted Jack Bradley, who still claims Louis never said a bad word about Glaser, even after Glaser died. But Jack did not like Glaser at all and was of the mindset that Glaser did work Louis too hard and take advantage of him. After Glaser died, Bradley was asked to write an article for the "Saturday Review" in July 1970 where he'd talk to black trumpeters Clark Terry and Ray Nance and white trumpeter Billy Butterfield about Louis. In the conversation (we have it on tape), Jack started dumping on Glaser, hoping that the other musicians would join in. They didn't. Here's my transcription of what happened next:

Clark Terry: “The only thing I could say about that situation is that Pops seemed to be very happy with the arrangement he had going with them. And I understand, I don’t know the exact figures, but I understand whatever his salary was, x amount of dollars, which was sufficient for him to live like a king, and x amount of dollars for his wife, Lucille, which was enough for her to live independently, as she chose. And the rest, the taxes and all the worries and so forth with keeping up with the government and staying abreast, staying clear of tax problems was left up to Joe Glaser. Now if he made a million dollars behind that, I understand that it was none of Pops’s business in the agreement. And if he didn’t make that, Pops expected his salary right on and I understand it was a very substantial one. If it went down the way I heard it went down, it ain’t a bad deal. It ain’t a bad deal."

Jack then said that Louis felt he wouldn't have made it as big without Glaser, which Jack felt was ludicrous. Ray Nance responded, " It’s possible because, I’m telling you, you’ve got to have good management. I don’t care how great you are. You’ve got to have good management. Good management goes hand in hand with success, with talent. Like we all know there’s a whole lot of people that are talented but they never get the right management. Or business! You might have a helluva idea for business but unless you have that business is done right with good management, you go bankrupt. You could go out of business without good management."

Billy Butterfield chimed in, "[Glaser] kept him clean all the time and he never got in any trouble with government and all of that like a lot of other guys."

Clark Terry: So when you think of it, who’s to say? The most important thing is that Pops is an intelligent man, although he wasn’t the most educated kid when he was brought up, he still was an intelligent person. And at the time he agreed to this agreement, I think he pretty much knew his way around. So I don’t think anybody put a pistol on him and made him do it.

And when Bradley finally complained about Louis working 50 years of one-nighters, Terry--who lived down the straight from Louis in Queens and used to hang with him in his den--shot him down with a quick, "He loved doing it."

You can say here I go again, black musicians talking to a white man, but like I said, Bradley was no fan of Glaser and didn't end up using a word of the above in his final story, lest he give Glaser any more praise.

But it's a fascinating conversation and I'm glad we're having it. Thanks, Pam!

Ricky