S'posin'

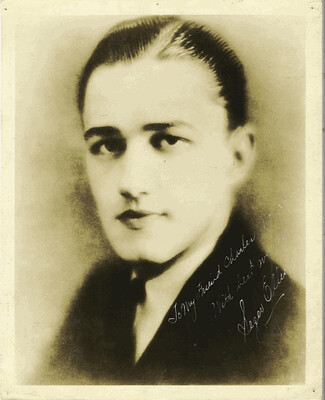

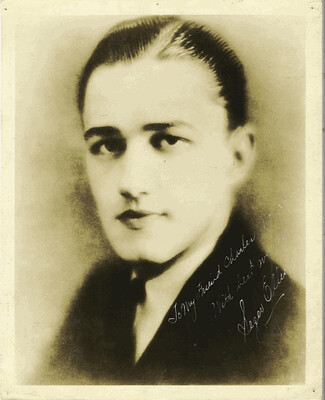

Seger Ellis

Recorded June 4, 1929

Track Time 3:17

Written by Andy Razaf and Paul Denniker

Recorded in New York City

Seger Ellis, vocal; Louis Armstrong, trumpet; Tommy Dorsey, trombone; Jimmy Dorsey,clarinet; Harry Hoffman, violin; Justin Ring, piano; Stan King, drums

Originally released on OKeh 41255

Currently available on CD: It's on volume five of Columbia’s old chronological series of Armstrong’s OKeh recordings, Louis in New York

Available on Itunes? Yes, on the same set

I’m honored to have jazz trombonist and historian David Sager as a regular reader of this blog (Sager, along with Doug Benson, was responsible for the Off the Record collection of King Oliver’s 1923 recordings with Armstrong, so Pops fanatics should thank him just for that. Check out his link, now in the right hand column). Last week, David wrote in asking if I’d tackle Pops’s 1929 recording of “S’posin’,” the great Andy Razaf-Paul Denniker standard. Since I do take requests (when I have enough time to field them), I’m going to discuss that track right now, as well as two later Armstrong live performances of the tune with vocals by Velma Middleton.

But let’s go back to 1929 and the Seger Ellis session, which was recorded 80 years ago last this month. If you remember my three-headed anniversary posting on “Knockin’ A Jug,” ”I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” and “Mahogany Hall Stomp” from March, I went into great detail about where Louis Armstrong was in his career in the beginning of 1929. He was still based in Chicago but he came to New York to do an engagement with Luis Russell’s orchestra, staying long enough to record the aforementioned numbers for OKeh, each one a bona fide classic.

After the session, Pops returned back to Chicago but it wasn’t long before he received an offer he couldn’t refuse to play in the revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates. Armstrong brought his entire band along and...well, I’m going to save that story until next month when I tackle the 80th anniversary of Armstrong’s first recording of “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” the tune that made Armstrong a hit during this period in New York. But before cutting that tune, OKeh, continuing a pattern that dated back to 1924, had Armstrong play the role of accompanist on two completely different recording sessions, one by the white pop singer Seger Ellis and one by the black blues singer Victoria Spivey.

So who was Seger Ellis? Ah, Seger Ellis. What a voice. You always remember the first time you hear Ellis’s dated vocals; it’s like remembering the first time you ever had bad clams. It only takes a few seconds of an Ellis performance to fully comprehend the effect Bing Crosby had on popular music of the period, as his popularity instantly made the Seger Ellis’s and Smith Ballew’s of the world sound like they were from another century. Today, one can listen to a 1930 Crosby vocal and appreciate every aspect of it. Today, it’s hard to listen to an Ellis record without laughing or cringing.

Now I know I sound like I’m being pretty hard on old Seger but the truth is I love the period flavor of his vocals. This, folks, is what Armstrong and Crosby fought to replace in rewriting the rules of American pop singing. But that doesn’t mean it didn’t exist so why not make the best of it? Ellis wasn’t expected to be Caruso or anything. Starting in 1927, Okeh began handing him pop tunes and Ellis did his best to sing them straight as an arrow, allowing many beloved songs to infiltrate the minds of most Americans who weren’t jazz fans. But Ellis, a pianist himself, always had good taste and made sure to hand-pick the musicians for his dates, always choosing from the cream of New York’s jazz crop. Hence, this 1929 “S’posin’” session, featuring a who’s who of the scene: there’s the Dorsey brothers (nuff said); drummer, Stan King, a veteran of the orchestras of Jean Goldkette, Roger Wolfe Kahn and Paul Whiteman’ violinist Harry Hoffman, who seemingly played with every major act of the period from Bing Crosby and The Boswell Sisters through later sessions with Frank Sinatra and Frankie Laine; classically trained pianist Justin Ring, part of the Joe Venuti-Eddie Lang crew, as well as a talented percussionist who led the Yellow Jackets on a series of OKeh records; and of course, our hero, Louis Armstrong.

The presence of Armstrong on the date might have raised some eyebrows the previous year but after the success of the interracial “Knockin’ a Jug” blues jam, record companies were a little more willing to let the races mingle. With Pops in town, who could blame Ellis for wanting the very best trumpeter around for his session, regardless of skin color? Ellis should be applauded for his choice.

So that’s that for the personnel. The song “S’posin’” was written by the team of Andy Razaf and Paul Denniker. Razaf, of course, is a legendary lyricist best known for his collaborations with Fats Waller (as we’ll see again when I get to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” next month). Denniker isn’t as well known but he did collaborate with Razaf on tunes like “Nero” and Shake Your Can, She’s Nine Months Gone” (that last one’s not exactly a standard). But “S’posin’” caught on in a big way, thanks to this version by Rudy Vallee. Vallee’s high, sweet voice is definitely a product of the period but I don’t know, it doesn’t inspire the laughter I have to suppress when I hear Ellis’s nasal offerings, sounding like his shoes are too tight...and an anvil just fell on his head. Anyway, here’s Rudy:

Vallee’s version was done for Victor on April 29, 1929. As soon as it began spreading, OKeh decided they needed a version of their own to compete and called ol’ reliable Seger Ellis to do the job. This is how it came out:

If you listened to the Vallee version, the tune was treated an uptempo, two-beat, perfectly suitable for a fox trot. Ellis decided to give it an ultra-sensitive, almost delicate rendering beginning with Hoffman’s sobbing violin and Ring’s pretty chording. Dorsey croons a couple of bars before Ellis’s entry, opening with the verse. When Ellis hits the main strain, the tempo picks up to the leisurely stroll of a medium pace. I dig this tempo a lot, even more than Vallee’s. King’s brushwork is a tasteful touch, too. Ellis sings it straight while the fearsome foursome of Armstrong’s muted trumpet, Hoffman’s violin, Jimmy Dorsey’s clarinet and Tommy Dorsey’s trombone, play a polyphonic obbligato. I have to admit that it’s kind of sloppy; there’s no distinct voice in the lead, attempts to play harmony notes seem quickly abandoned and everyone plays at the same hushed volume level, sounding a bit like a bunch of drunks at a bar trying to croon a lullaby. Jimmy Dorsey sticks to the low register of his clarinet, Hoffman plays like he’s the only one in the studio and Armstrong does his best to pick his spots (did you catch a patented Pops lick after Ellis sings the line “S’posin I should say for you I yearn”?)

As Ellis nears the end of his chorus, the band almost stops playing in tempo. It almost sounds like it’s about to end but thankfully, it’s just about to really begin. Ellis sings his last word and Pops immediately breaks through with a break as if to say, “Back off, boys! I’ll take it from here.” It’s a great break, topped off by a perfectly placed cymbal accent by King. Armstrong then goes into an absolutely delightful solo, backed by the rocking press rolls of King’s drums. As I’ve made the point 9,000 times, Armstrong liked loud, emphatic drumming and he obviously dug what King was putting down.

Finally, the other musicians achieve a kind of quiet cohesion in the background, offering Armstrong a lovely bed of harmonies to float over. Jimmy Dorsey even continues to play the melody quietly in the lower register of his clarinet, making Armstrong’s improvisations seem that much more startling. It’s a seemingly relaxed outing, but there’s a special tension to Armstrong’s muted playing. He’s very lyrical but there’s also a certain edge that makes the listener anxious for the trumpeter to just erupt with some dazzling run to obliterate the melody. Armstrong starts off with some impressive peckin’ and pokin’ in his solo, very reminiscent of his work on “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” He then settles down a bit in the middle before hitting a few beautiful high Ab’s in the eleventh bar of the solo. Obviously liking the fit of the note, he pauses for a second, then resumes by playing the exact same ascending run up to some more Ab’s, spinning it off into another perfectly weighted phrase. Then finally, after another pause, and knowing time’s running out, mount Armstrong finally erupts into a dizzying double-timed run, closing his solo with a beautiful chunk of vintage 1929 Pops. There’s a helluva lot of information in those 16 bars, my friends.

Ellis then returns and--are my ears deceiving me?--actually starts swinging a bit, boiling down his first phrase to just two alternating notes, a la Armstrong. Geez, that didn’t take long, huh? Ellis, clearly thriving from Pops’s vibe, does sound looser as he winds up the record. The other instrumentalists, perhaps in awe of Armstrong the great, stay hushed for a while but finally Hoffman runs in to play the melody along with Ellis’s straight-out-of-Kermit-the-Frog vocal. The end of the record is positively charming. Yeah, it’s not exactly Louis or Bing singing (or Red McKenzie for that matter) but if you love 1920s music, you have to have some affection for Ellis’s offerings.

Flash forward almost 20 years. Armstrong is now leading the All Stars and his popularity is steadily climbing to all-time highs. His female vocalist, of course, was the great Velma Middleton. Okay, she wasn’t exactly the greatest singer, but she was a terrific entertainer and had an unbeatable chemistry with Pops. Today, Velma is best known for those hilarious, double-entendre filled duets with Armstrong on numbers like “That’s My Desire” and “Baby It’s Cold Outside.” She’s also known for doing splits on her blues features, quite a feat for a woman as heavy as Velma. But in the early days of the group, she was a veritable standard machine.

By the mid-50s, the All Stars became a huge concert attraction and that’s when Velma streamlined her sets a bit. You almost always knew what you were going to get when Velma came out in that period: a blues, a duet with Louis, perhaps “Ko Ko Mo” and that was about it. But in the late 40s and early 50s, the All Stars played a lot of nightclubs, extended engagements that often featured multiple sets each evening. Those were the days when one could really appreciate how large the All Stars’s band book really was. And Velma did much more than sing the blues. She tackled numbers like “I Cried For You,” “Little White Lies,” “Together,” “Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me,” “Blue Skies” and yes, “Sposin’.” Fortunately, two examples of “S’posin’” exist, both of them pretty rare. For starters, here’s how the tune sounded at The Click in Philadelphia on September 18, 1948. This is the truly all star edition of the group with Jack Teagarden on trombone, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Earl Hines on piano, Arvell Shaw on bass and, making his presence felt immediately, the dancing drums of Big Sid Catlett:

All of Velma’s features on standards usually featured an identical arrangement: the band plays a chorus of melody, Pops in the lead, Velma sings one straight, Velma sings one a little looser, the band swoops in for a half a chorus, then Velma takes it out. “S’posin’” is no exception. Pops’s lead playing, sticking pretty close to the melody, is beautiful, getting perfect backing from Catlett throughout. Bigard and Teagarden don’t make much of an impact in the ensemble but it’s no big deal since Pops’s lead is really the main event.

Velma sounds good in her vocal, getting nice backing from both Pops and an ornate Bigard (Teagarden takes over in Velma’s second chorus). Armstrong gets in a humorous vocal aside in Velma’s second helping, responding to her line, “S’posin I should say for you I yearn” by barking a response, “Why don’t you say it?” I always tense up as Velma winds down, awaiting the explosion of sound that’s about to come through my speakers. Catlett really starts the thunder, though Armstrong doesn’t rush, beginning his improvisation with a very relaxed opening. The tempo is really a perfect one, I must say, as I can’t stop patting my foot as I listen to it. Pops is completely in command, still phrasing everything in the most rhythmically complex way as possible, but now he shows off his new and improved range, hitting a high concert D and squeezing the life out of it, a triumphant moment. Armstrong’s obbligato quiets down as he lets Velma take it out on her own. A terrific performance.

Now lets flash forward to May 21, 1955 and an unissed broadcast from Basin Street in New York City. Arvell Shaw was still in the band, as well as a quickly running-out-of-gas Bigard but otherwise, the personnel was completely different. This is the classic “W.C. Handy” version of the All Stars with Trummy Young on trombone, Billy Kyle on piano and Barrett Deems on drums. This group could be known to swing almost violently behind Pops, something I love ‘em for. Thus, the tempo for this version of “S’posin’” is slightly faster than the one from 1948 and played with a little more oomph, more appropriate for foot stomping, rather than just patting. Give it a listen:

Clearly, the tune wasn’t one that was played very often by the group because Kyle sounds like he’s in the middle of a 16-bar introduction when Armstrong and the group steamrolls him after only eight bars (again, the Basin Street gigs were extended engagements so Armstrong was more free to dip into the depths of his book). As for Pops, stand back. I’ve always argued that in mid-50s, Armstrong experienced another prime period of blowing, sounding even stronger than he did in the late 40s. Just listen to the lead playing, featuring a touch of “Honeysuckle Rose” and a high octane ending, playing the melody an octave higher than usual. I love that 1948 performance but Pops sounds much better here (he even cracked a note in the earlier version’s opening ensemble). Armstrong even takes over full obbligato chores, quoting “Melancholy Baby” twice in Velma’s second chorus. And listen to that obbligato, featuring all sorts of modern touches towards the end, Armstrong half-valving certain notes and playing a descending motif after Velma sings the line “out of turn” that’s out of Red Allen’s playbook (or should I reverse that?) Even Velma sounds looser and swings harder; this group could inspire anybody to sweat and swing (except Barney who was bored out of his mind and couldn’t hide it).

Already it’s been a great performance but the group’s half-chorus interlude is simply stunning. I might have to reverse my judgement that the group didn’t play this tune very often because Armstrong and Trummy are 100% locked in with the repeated notes during the turnaround. And remember how I said that Armstrong approached his solo on the 1929 version with a feel similar to his solo on “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”? Well, here he eliminates any doubts and just quotes that tune verbatim, a terrific touch. Are Catlett’s fills and accents missed? Sure, but Deems was a rock and Pops clearly thrived from his power. The group stomps away with incredible force and Armstrong plays like a man possessed. Again, though, he turns his volume all the way down upon Velma’s reentrance. The ending on the 1948 version was a little shaky but by this time, it’s as tight as a drum with Velma taking a false ending, going into a neat little tag. Pops hits the high note and it’s all over. A tremendously rare performance (you’ll only hear it here, folks!) but I think it’s a wonderful portrait of the mid-50s group at full power.

S’all for now. Thanks again to David Sager for the suggestion as I think Pops sounded dynamite on all three versions. I should be able to whip up one more entry before the week ends...til then!

Recorded June 4, 1929

Track Time 3:17

Written by Andy Razaf and Paul Denniker

Recorded in New York City

Seger Ellis, vocal; Louis Armstrong, trumpet; Tommy Dorsey, trombone; Jimmy Dorsey,clarinet; Harry Hoffman, violin; Justin Ring, piano; Stan King, drums

Originally released on OKeh 41255

Currently available on CD: It's on volume five of Columbia’s old chronological series of Armstrong’s OKeh recordings, Louis in New York

Available on Itunes? Yes, on the same set

I’m honored to have jazz trombonist and historian David Sager as a regular reader of this blog (Sager, along with Doug Benson, was responsible for the Off the Record collection of King Oliver’s 1923 recordings with Armstrong, so Pops fanatics should thank him just for that. Check out his link, now in the right hand column). Last week, David wrote in asking if I’d tackle Pops’s 1929 recording of “S’posin’,” the great Andy Razaf-Paul Denniker standard. Since I do take requests (when I have enough time to field them), I’m going to discuss that track right now, as well as two later Armstrong live performances of the tune with vocals by Velma Middleton.

But let’s go back to 1929 and the Seger Ellis session, which was recorded 80 years ago last this month. If you remember my three-headed anniversary posting on “Knockin’ A Jug,” ”I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” and “Mahogany Hall Stomp” from March, I went into great detail about where Louis Armstrong was in his career in the beginning of 1929. He was still based in Chicago but he came to New York to do an engagement with Luis Russell’s orchestra, staying long enough to record the aforementioned numbers for OKeh, each one a bona fide classic.

After the session, Pops returned back to Chicago but it wasn’t long before he received an offer he couldn’t refuse to play in the revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates. Armstrong brought his entire band along and...well, I’m going to save that story until next month when I tackle the 80th anniversary of Armstrong’s first recording of “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” the tune that made Armstrong a hit during this period in New York. But before cutting that tune, OKeh, continuing a pattern that dated back to 1924, had Armstrong play the role of accompanist on two completely different recording sessions, one by the white pop singer Seger Ellis and one by the black blues singer Victoria Spivey.

So who was Seger Ellis? Ah, Seger Ellis. What a voice. You always remember the first time you hear Ellis’s dated vocals; it’s like remembering the first time you ever had bad clams. It only takes a few seconds of an Ellis performance to fully comprehend the effect Bing Crosby had on popular music of the period, as his popularity instantly made the Seger Ellis’s and Smith Ballew’s of the world sound like they were from another century. Today, one can listen to a 1930 Crosby vocal and appreciate every aspect of it. Today, it’s hard to listen to an Ellis record without laughing or cringing.

Now I know I sound like I’m being pretty hard on old Seger but the truth is I love the period flavor of his vocals. This, folks, is what Armstrong and Crosby fought to replace in rewriting the rules of American pop singing. But that doesn’t mean it didn’t exist so why not make the best of it? Ellis wasn’t expected to be Caruso or anything. Starting in 1927, Okeh began handing him pop tunes and Ellis did his best to sing them straight as an arrow, allowing many beloved songs to infiltrate the minds of most Americans who weren’t jazz fans. But Ellis, a pianist himself, always had good taste and made sure to hand-pick the musicians for his dates, always choosing from the cream of New York’s jazz crop. Hence, this 1929 “S’posin’” session, featuring a who’s who of the scene: there’s the Dorsey brothers (nuff said); drummer, Stan King, a veteran of the orchestras of Jean Goldkette, Roger Wolfe Kahn and Paul Whiteman’ violinist Harry Hoffman, who seemingly played with every major act of the period from Bing Crosby and The Boswell Sisters through later sessions with Frank Sinatra and Frankie Laine; classically trained pianist Justin Ring, part of the Joe Venuti-Eddie Lang crew, as well as a talented percussionist who led the Yellow Jackets on a series of OKeh records; and of course, our hero, Louis Armstrong.

The presence of Armstrong on the date might have raised some eyebrows the previous year but after the success of the interracial “Knockin’ a Jug” blues jam, record companies were a little more willing to let the races mingle. With Pops in town, who could blame Ellis for wanting the very best trumpeter around for his session, regardless of skin color? Ellis should be applauded for his choice.

So that’s that for the personnel. The song “S’posin’” was written by the team of Andy Razaf and Paul Denniker. Razaf, of course, is a legendary lyricist best known for his collaborations with Fats Waller (as we’ll see again when I get to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” next month). Denniker isn’t as well known but he did collaborate with Razaf on tunes like “Nero” and Shake Your Can, She’s Nine Months Gone” (that last one’s not exactly a standard). But “S’posin’” caught on in a big way, thanks to this version by Rudy Vallee. Vallee’s high, sweet voice is definitely a product of the period but I don’t know, it doesn’t inspire the laughter I have to suppress when I hear Ellis’s nasal offerings, sounding like his shoes are too tight...and an anvil just fell on his head. Anyway, here’s Rudy:

Vallee’s version was done for Victor on April 29, 1929. As soon as it began spreading, OKeh decided they needed a version of their own to compete and called ol’ reliable Seger Ellis to do the job. This is how it came out:

If you listened to the Vallee version, the tune was treated an uptempo, two-beat, perfectly suitable for a fox trot. Ellis decided to give it an ultra-sensitive, almost delicate rendering beginning with Hoffman’s sobbing violin and Ring’s pretty chording. Dorsey croons a couple of bars before Ellis’s entry, opening with the verse. When Ellis hits the main strain, the tempo picks up to the leisurely stroll of a medium pace. I dig this tempo a lot, even more than Vallee’s. King’s brushwork is a tasteful touch, too. Ellis sings it straight while the fearsome foursome of Armstrong’s muted trumpet, Hoffman’s violin, Jimmy Dorsey’s clarinet and Tommy Dorsey’s trombone, play a polyphonic obbligato. I have to admit that it’s kind of sloppy; there’s no distinct voice in the lead, attempts to play harmony notes seem quickly abandoned and everyone plays at the same hushed volume level, sounding a bit like a bunch of drunks at a bar trying to croon a lullaby. Jimmy Dorsey sticks to the low register of his clarinet, Hoffman plays like he’s the only one in the studio and Armstrong does his best to pick his spots (did you catch a patented Pops lick after Ellis sings the line “S’posin I should say for you I yearn”?)

As Ellis nears the end of his chorus, the band almost stops playing in tempo. It almost sounds like it’s about to end but thankfully, it’s just about to really begin. Ellis sings his last word and Pops immediately breaks through with a break as if to say, “Back off, boys! I’ll take it from here.” It’s a great break, topped off by a perfectly placed cymbal accent by King. Armstrong then goes into an absolutely delightful solo, backed by the rocking press rolls of King’s drums. As I’ve made the point 9,000 times, Armstrong liked loud, emphatic drumming and he obviously dug what King was putting down.

Finally, the other musicians achieve a kind of quiet cohesion in the background, offering Armstrong a lovely bed of harmonies to float over. Jimmy Dorsey even continues to play the melody quietly in the lower register of his clarinet, making Armstrong’s improvisations seem that much more startling. It’s a seemingly relaxed outing, but there’s a special tension to Armstrong’s muted playing. He’s very lyrical but there’s also a certain edge that makes the listener anxious for the trumpeter to just erupt with some dazzling run to obliterate the melody. Armstrong starts off with some impressive peckin’ and pokin’ in his solo, very reminiscent of his work on “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” He then settles down a bit in the middle before hitting a few beautiful high Ab’s in the eleventh bar of the solo. Obviously liking the fit of the note, he pauses for a second, then resumes by playing the exact same ascending run up to some more Ab’s, spinning it off into another perfectly weighted phrase. Then finally, after another pause, and knowing time’s running out, mount Armstrong finally erupts into a dizzying double-timed run, closing his solo with a beautiful chunk of vintage 1929 Pops. There’s a helluva lot of information in those 16 bars, my friends.

Ellis then returns and--are my ears deceiving me?--actually starts swinging a bit, boiling down his first phrase to just two alternating notes, a la Armstrong. Geez, that didn’t take long, huh? Ellis, clearly thriving from Pops’s vibe, does sound looser as he winds up the record. The other instrumentalists, perhaps in awe of Armstrong the great, stay hushed for a while but finally Hoffman runs in to play the melody along with Ellis’s straight-out-of-Kermit-the-Frog vocal. The end of the record is positively charming. Yeah, it’s not exactly Louis or Bing singing (or Red McKenzie for that matter) but if you love 1920s music, you have to have some affection for Ellis’s offerings.

Flash forward almost 20 years. Armstrong is now leading the All Stars and his popularity is steadily climbing to all-time highs. His female vocalist, of course, was the great Velma Middleton. Okay, she wasn’t exactly the greatest singer, but she was a terrific entertainer and had an unbeatable chemistry with Pops. Today, Velma is best known for those hilarious, double-entendre filled duets with Armstrong on numbers like “That’s My Desire” and “Baby It’s Cold Outside.” She’s also known for doing splits on her blues features, quite a feat for a woman as heavy as Velma. But in the early days of the group, she was a veritable standard machine.

By the mid-50s, the All Stars became a huge concert attraction and that’s when Velma streamlined her sets a bit. You almost always knew what you were going to get when Velma came out in that period: a blues, a duet with Louis, perhaps “Ko Ko Mo” and that was about it. But in the late 40s and early 50s, the All Stars played a lot of nightclubs, extended engagements that often featured multiple sets each evening. Those were the days when one could really appreciate how large the All Stars’s band book really was. And Velma did much more than sing the blues. She tackled numbers like “I Cried For You,” “Little White Lies,” “Together,” “Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me,” “Blue Skies” and yes, “Sposin’.” Fortunately, two examples of “S’posin’” exist, both of them pretty rare. For starters, here’s how the tune sounded at The Click in Philadelphia on September 18, 1948. This is the truly all star edition of the group with Jack Teagarden on trombone, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Earl Hines on piano, Arvell Shaw on bass and, making his presence felt immediately, the dancing drums of Big Sid Catlett:

All of Velma’s features on standards usually featured an identical arrangement: the band plays a chorus of melody, Pops in the lead, Velma sings one straight, Velma sings one a little looser, the band swoops in for a half a chorus, then Velma takes it out. “S’posin’” is no exception. Pops’s lead playing, sticking pretty close to the melody, is beautiful, getting perfect backing from Catlett throughout. Bigard and Teagarden don’t make much of an impact in the ensemble but it’s no big deal since Pops’s lead is really the main event.

Velma sounds good in her vocal, getting nice backing from both Pops and an ornate Bigard (Teagarden takes over in Velma’s second chorus). Armstrong gets in a humorous vocal aside in Velma’s second helping, responding to her line, “S’posin I should say for you I yearn” by barking a response, “Why don’t you say it?” I always tense up as Velma winds down, awaiting the explosion of sound that’s about to come through my speakers. Catlett really starts the thunder, though Armstrong doesn’t rush, beginning his improvisation with a very relaxed opening. The tempo is really a perfect one, I must say, as I can’t stop patting my foot as I listen to it. Pops is completely in command, still phrasing everything in the most rhythmically complex way as possible, but now he shows off his new and improved range, hitting a high concert D and squeezing the life out of it, a triumphant moment. Armstrong’s obbligato quiets down as he lets Velma take it out on her own. A terrific performance.

Now lets flash forward to May 21, 1955 and an unissed broadcast from Basin Street in New York City. Arvell Shaw was still in the band, as well as a quickly running-out-of-gas Bigard but otherwise, the personnel was completely different. This is the classic “W.C. Handy” version of the All Stars with Trummy Young on trombone, Billy Kyle on piano and Barrett Deems on drums. This group could be known to swing almost violently behind Pops, something I love ‘em for. Thus, the tempo for this version of “S’posin’” is slightly faster than the one from 1948 and played with a little more oomph, more appropriate for foot stomping, rather than just patting. Give it a listen:

Clearly, the tune wasn’t one that was played very often by the group because Kyle sounds like he’s in the middle of a 16-bar introduction when Armstrong and the group steamrolls him after only eight bars (again, the Basin Street gigs were extended engagements so Armstrong was more free to dip into the depths of his book). As for Pops, stand back. I’ve always argued that in mid-50s, Armstrong experienced another prime period of blowing, sounding even stronger than he did in the late 40s. Just listen to the lead playing, featuring a touch of “Honeysuckle Rose” and a high octane ending, playing the melody an octave higher than usual. I love that 1948 performance but Pops sounds much better here (he even cracked a note in the earlier version’s opening ensemble). Armstrong even takes over full obbligato chores, quoting “Melancholy Baby” twice in Velma’s second chorus. And listen to that obbligato, featuring all sorts of modern touches towards the end, Armstrong half-valving certain notes and playing a descending motif after Velma sings the line “out of turn” that’s out of Red Allen’s playbook (or should I reverse that?) Even Velma sounds looser and swings harder; this group could inspire anybody to sweat and swing (except Barney who was bored out of his mind and couldn’t hide it).

Already it’s been a great performance but the group’s half-chorus interlude is simply stunning. I might have to reverse my judgement that the group didn’t play this tune very often because Armstrong and Trummy are 100% locked in with the repeated notes during the turnaround. And remember how I said that Armstrong approached his solo on the 1929 version with a feel similar to his solo on “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”? Well, here he eliminates any doubts and just quotes that tune verbatim, a terrific touch. Are Catlett’s fills and accents missed? Sure, but Deems was a rock and Pops clearly thrived from his power. The group stomps away with incredible force and Armstrong plays like a man possessed. Again, though, he turns his volume all the way down upon Velma’s reentrance. The ending on the 1948 version was a little shaky but by this time, it’s as tight as a drum with Velma taking a false ending, going into a neat little tag. Pops hits the high note and it’s all over. A tremendously rare performance (you’ll only hear it here, folks!) but I think it’s a wonderful portrait of the mid-50s group at full power.

S’all for now. Thanks again to David Sager for the suggestion as I think Pops sounded dynamite on all three versions. I should be able to whip up one more entry before the week ends...til then!

Comments